Poirot Score: 86

Crooked House

☆☆☆☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

This is one of Christie’s genre-extending novels. The solution is bold and presents narrative problems that Christie solves and in solving she develops a new kind of clue. A reader who guesses the solution for the right reasons will be pretty certain that he or she has done so, but the solution is by no means obvious. It was one of Christie’s own favourites amongst her oeuvre. So why don’t we give it an even higher score? We have marked it down a little because overall it is not so engaging, not so funny perhaps, as many of her novels. The problem may be that there is none of her famous characters to liven up the dialogue and the action.

Click here for full review (spoilers ahead)

Trivia

An Eton crop and the Lambert Institute, Gower Street

She [Clemency Leonides] was about fifty, I suppose; her hair was grey, cut very short in what was almost an Eton crop but which grew so beautifully on her small well-shaped head that it had none of the ugliness I have always associated with that particular cut.

Part VII

The Eton crop was one of the styles of short hair for women that were popular in the 1920s. The short-haired styles for either men or women are generally known as ‘bobs’. The term ‘crop’ is reserved for women’s short-haired styles and the Eton Crop was one of the shortest, modelled on the boys at Eton school who wore their hair somewhat longer than most boys at the time. In The Sittaford Mystery Emily Trefusis is described as having shingled hair which is another short-haired style (see Trivia for The Sittaford Mystery). If Clemency is about 50 years old and the novel is set in the late 1940s then she would have been in her 20s when the Eton crop was popular and perhaps she had kept to that style ever since. The narrator generally does not like the Eton crop, perhaps thinking it is more of an Eton mess.

Clemency works at “the Lambert Institute in Gower Street” on ‘radiation effects of atomic disintegration”. Inspector Taverner assumes her work is to do with the atomic bomb but she quickly corrects him: “The work has nothing destructive about it. The Institute is carrying out experiments on the therapeutic effects”. During the Second World War most research on radiation was focused on the harmful effects, but this was changing by the late 1940s as interest shifted back to the pre-war concern with the possible therapeutic benefits. The Lambert Institute is fictional but its location in Gower Street suggests that it was attached to University College, London – both the main University site and the site where University College Hospital was located from 1906 until 2005 are in Gower Street. The old Hospital site is now occupied by the Cruciform Building and the Wolfson Builing for Bioemedical Research. The Hospital now occupies a modern building in nearby Euston Road.

Athene Seyler and Arsenic and Old Lace

The titian hair was piled up high on her head in an Edwardian coiffure, and she was dressed in a well-cut dark-grey coat and skirt with a delicately pleated pale mauve shirt fastened at the neck by a small cameo brooch. For the first time I was aware of the charm of her delightfully tip-tilted nose. I was faintly reminded of Athene Seyler – and it seemed quite impossible to believe that this was the tempestuous creature in the peach négligé.

The narrator’s description of the actress Magda West – wife of Phillip Leonides. Chapter VII

She’s no sense of time. She’s reading a new play of Vavasour Jones called The Woman Disposes. It’s a funny play about murder – a female Bluebeard – cribbed from Arsenic and Old Lace if you ask me, but it’s got a good woman’s part, a woman who’s got a mania for being a widow.

Sophia Leonides about her mother, Magda West. Chapter XXV

These two passages, although far apart in the novel, are both descriptions of the histrionic mother of Sophia, Eustace and Josephine, an actress whose stage name is Magda West. When I was a teenager living in London I remember the posters, and the media attention, surrounding the run at the Vaudeville Theatre in The Strand of Arsenic and Old Lace. This was in 1966, seventeen years after the publication of Crooked House. The play had not been staged in London at a major theatre before. Two of the main characters are the murderous spinster aunts of the Brewster family. Part of the excitement, in London, was due to the actresses playing these parts: Dame Sybil Thorndike and Athene Seyler. Thorndike together with Edith Evans were doyennes of the English stage at the time. Thorndike was 83 years old and this was to be her farewell London theatrical performance (although she did attend her 90th birthday celebration in 1972 at The Haymarket Theatre). Thorndike’s husband, Sir Lewis Casson, was also in the cast. They are amongst a very few couples both of whom were honoured with a ‘knighthood’ (or ‘damehood’), Dame Agatha Christie and Sir Max Mallowan being another example of such a couple. One of Sybil Thorndike’s friends was Athene Seyler, another much-loved mainly stage actress, seven years younger than Thorndike. Her first professional stage appearance was in 1909 as Rosalind in As You Like It, a play that Christie refers to several times in her books [e.g. in Murder on the Orient Express and A Murder is Announced] and Christie probably named her daughter Rosalind after Shakespeare’s feisty heroine. Seyler, like Edith Evans, was also known for her portrayal of Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest. Seyler gave a talk about her career in acting at London’s National Theatre in 1990. She was then aged 101 years. In writing of both Athene Seyler and Arsenic and Old Lace Christie seems to have been prescient.

Arsenic and Old Lace, a black comedy, was written in 1939 by Joseph Kesselring and was premiered on Broadway in 1941. It ran until 1944 after almost 1500 performances. The plot centres on the, very odd, Brewster family. The title refers to Martha and Abby Brewster, the two sweet spinster aunts – the old lace – and to the arsenic (along with strychnine and a pinch of cyanide) with which they lace the home-made elderberry wine that they give to lonely old men who have nothing to live for. They consider their work, their murders, as acts of charity. The play was made into a film in 1944 starring Cary Grant which is probably how Christie knew of it.

In Crooked House, Vavasour Jones is the name Christie gives to the fictional writer of a play in which Magda hopes to be the star, The Woman Disposes, a play based loosely, it seems, on the real murder of Percy Thompson, husband of Edith Thompson.

Edith Thompson

You know, Phillip, I really believe that this would be a wonderful opportunity to put on the Edith Thompson play. This murder would give us a lot of advance publicity. …. I know they say I must always play comedy because of my nose – but you know there’s quite a lot of comedy to be got out of Edith Thompson – I don’t think the author realised that – comedy always heightens the suspense. I know just how I’d play it [i.e. the part of Edith Thompson] – commonplace, silly, make-believe up to the last minute and then

Magda West to her husband Phillip Leonides. Chapter VI

Mother won’t hear of giving him any [money] because she wants Father to put up the money for Edith Thompson [i.e. a play about Edith Thompson]. Do you know about Edith Thompson? She was married, but she didn’t like her husband. She was in love with a young man called Bywaters who came off a ship and he went down a different street after the theatre and stabbed him in the back..

Josephine talking to the narrator, Charles Hayward, chapter XIII

Although Magda probably never played the part of Edith Thompson, Francesca Annis did, in 1973 in the TV drama A pin to see the peepshow. Annis has also played more Christie characters than most. Back in 1964 she was Sheila Upward in the film, Murder Most Foul, a version of Christie’s 1952 novel Mrs McGinty’s Deadin which the Poirot of the novel is replaced by Miss Marple. It is one of the four films in which Margaret Rutherford played Miss Marple. In 1983 Annis played Christie’s detective Tuppence in the TV series Partners in Crime, and a few years before that, in 1980, she was Lady Frances Derwent, an aristocratic version of Tuppence, in Why didn’t they ask Evans?

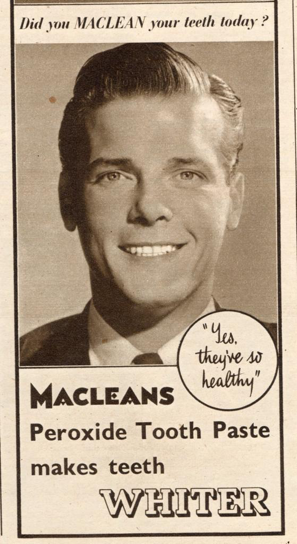

Edith Thompson was hanged for murder on 9th January 1923 at Holloway Prison in London. Nine women were hanged for murder after that before capital punishment was abolished for murder in Great Britain in 1969. The hangman of Edith Thompson was John Ellis, who committed suicide in 1932.

At the time of the murder Edith Thompson was 28 years old. She was married to Percy Thompson, aged 32 years, who was a shipping clerk. She was having an affair with 20 year old Frederick Bywaters, a ship’s steward with P&O (The Peninsular and Orient Steam Navigation Company, which by the 1920s, if one includes the companies in which it had a controlling interest, had a fleet of over 500 ships). On October 4th 1922, just after midnight, Edith Thompson and her husband were coming back to their home in Ilford, Essex after an evening at the theatre in London. Frederick Bywaters jumped out from the shadows and stabbed Percy Thompson who died from the wound.

Frederick Bywaters admitted the killing. Throughout the court proceedings, and after the sentence, he insisted that Edith Thompson had not been a party to the murder. But in letters to Frederick Bywaters, Edith Thompson wrote that she had tried to kill her husband by poisoning and by administering broken glass in his food. She also implored ‘Freddy’ to do something desperate. At the trial, and against the advice of her barrister, Sir Henry Curtis-Bennett, Edith Thompson took the witness stand and made a bad impression on judge and jury. Both she and Frederick Bywaters were found guilty of murder and, as was the law of the day, the judge pronounced the death sentence. A petition, signed by almost a million people, against the death sentence failed to convince the Home Secretary, William Bridgeman, that he should grant a reprieve.

There had never been doubt that Frederick Bywaters, and only Frederick Bywaters, had physically attacked Percy Thompson. Edith Thompson was found guilty as a ‘principal in the second degree’. The ‘principal in the first degree’ is the person (or people) who actually perpetrates the crime (Frederick Bywaters in this case). The ‘principal in the second degree’ is a person who helps the principal in the first degree and who is present at the crime. These are in contrast with an ‘accessory before the fact’ – that is a person who assists or encourages a principal to commit the crime but is not present at the crime – and an ‘accessory after the fact’ who is a person who knows a crime has been committed and helps an offender to escape detection, capture or punishment.

Many view the conviction of Edith Thompson for murder as a miscarriage of justice. It is widely considered that the evidence that she knew of the intended attack beforehand, or that she had planned the murder or even incited Frederick Bywaters to carry it out, does not amount to ‘proof beyond reasonable doubt’. Bywaters himself denied that she was in any way involved and her letters to Bywaters, many of which were too steamy to be allowed to be quoted in court, have been interpreted as products of Edith Thompson’s fecund imagination rather than as providing evidence of what she had done or of her inciting Frederick Bywaters to murder. Her claims to having poisoned her husband are seriously doubted – autopsy after his death showed no evidence of poisoning, by ground glass or other substances. On one view, her conviction owed more to her adultery and overt sexuality than to any part she played in the murder of her husband.

In 1952, a few years after the publication of Crooked House, Lewis Broad wrote a book called The Innocence of Edith Thompson: a Study in Old Bailey Justice and in 1988 René Weis published a biography of Thompson called Criminal Justice: the True Story of Edith Thompson. Much earlier, in 1930, Dorothy L Sayers (together with Robert Eustace) published a novel (Sayers’ only crime novel without the character of Lord Peter Wimsey) called The Documents in the Case which may have been loosely based on the Thompson case. In that novel a wife writes letters to her lover that lead him to murder her husband. Earlier still, in 1923 F. Tennyson Jesse, a great-niece of Alfred Lord Tennyson, wrote a novel based on the Thompson and Bywaters case called A Pin to see the Peepshow. The novel was dramatised as a two-act play by Tennyson Jesse’s husband H.M. Harwood. Peter Coles directed the play. He was also the first director of Christie’s The Mousetrap. The Lord Chamberlain (who could censor plays for public performance in England at the time) refused to give the dramatised version of A Pin to see the Peepshow a licence because of the possibility that the play might upset the living relatives of Thompson and Bywaters, so Coles first produced it at a private club in London in May 1951. Two years later he took it to Broadway where it opened on September 17th 1953. The part of Julia Almond (the Edith Thompson character) was played by Peter Coles’ wife, Joan Miller. Leonard Carr, the Frederick Bywaters character, was played by a certain Roger Moore, later of James Bond fame: his Broadway debut.

Moore turned up at the theatre for the play’s second night, on September 18th, to find that due to poor reviews the play had closed, after a single performance. Being at a loose end Moore decided to go to the cinema to see the film, The Robe, starring Richard Burton and Jean Simmons.

The novel, A Pin for the Peepshow, was again adapted, this time in four episodes for TV by Elaine Morgan, and it was that dramatisation in which Francesca Annis played Julia Almond – the part based on Edith Thompson.