Poirot Score: 85

A Murder is Announced

☆☆☆☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

The third published Miss Marple novel, twenty years after her debut. This is technically one of Christie’s most brilliant novels. There are many clues of very different types some of which can only be interpreted in the light of other clues. The misdirections are clever and varied. There are many puzzles for the reader to solve as the novel unfolds. The set-up is engaging: a murder announced in the local newspaper before it happens. The novel gives a vivid picture of post-war English village life, the attempts to get around rationing, the newspapers, and includes Christie’s first lesbian couple in a long-term relationship. The central plot devices are good but Christie has used them in one form or another before, and Miss Marple does not bring out Christie’s talent for comedy as well as Poirot does.

Click here for full review (spoilers ahead)

Trivia

A.R.P days (see also Trivia for N or M, and The Body in the Library

Incident! Reminds me of my A.R.P.days. Saw some incidents then, I can tell you. Where was I when the shooting started? That what you want to know?

Miss Hinchcliffe talking to Inspector Craddock

A.R.P. stands for Air Raid Precautions and refers to an organisation founded in 1924 in the United Kingdom to reduce deaths and damage from bombing from the air. The experience of the destruction caused by German bombing during the First World War was the stimulus for setting up the A.R.P. Preliminary calculations suggested that in the setting of another war, bomber aircraft would cause enormous casualties especially from the bombing of cities such as London. In the prelude to the Second World War the A.R.P became more active.

In 1938 JBS Haldane wrote a book called A.R.P. in which he argued that the British government was not doing enough and was not doing the right things in preparing for bombing raids on Britain. Haldane was a polymath scientist. He followed in the footsteps of his father, J.S. Haldane in often experimenting on himself, and in making major contributions to many areas of science and particularly population genetics. His father had, amongst other things, invented the first gas mask in response to the use of poisonous gas as a weapon by the Germans in the First World War. JBS Haldane, two years younger than Agatha Christie, was brought up in Oxford, and was a student at New College a few years before Max Mallowan (Christie’s second husband). He carried out research in Oxford, Cambridge and became Professor at University College, London.

During the Second World War the A.R.P was responsible for all aspects of protection against air raids: the provision of gas masks, maintaining air-raid shelters and rescuing people after raids.

Pekes in the high hall garden

Pekes in the high hall garden, (said Edmund)

When twilight was falling (only it’s eleven a.m)

Phil, Phil, Phil, Phil,

They were crying and calling

Chapter 12 section 1

Edmund, the left-wing intellectual young man, is talking to Phillipa Haymes, with whom he is in love. Edmund is humorously re-working a poem by one of that Christie’s favourites, Tennyson. The poem quoted is called Birds in the high hall garden (Tennyson’s Maud, section XII). The original goes:

Birds in the high Hall-garden

When twilight was falling,

Maud, Maud, Maud, Maud,

They were crying and calling.

This is one of the poems that Somervell set to music in his song cycle, Maud, from which Christie has previously quoted (see Trivia for Sparkling Cyanide). This poem has also been set to music by Delius. Edmund goes on to briefly (mis)quote from Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost (‘When greasy Joan the pot doth keel’). A few pages earlier, when Phillipa seemed to reject his advances he also quoted from Tennyson’s Maud cycle, “Faultily faultless, icily regular, splendidly null’.

Tiglath Pileser

As the flex pulled across the table, Tiglath Pileser the cat leapt upon it and bit and clawed it violently.

Chapter 19

Mrs ‘Bunch’ Harmon is the wife of the vicar in Chipping Cleghorn and a friend of Miss Marple’s. Tiglath Pileser is Bunch’s cat. When Christie likens a character to a cat this normally has negative connotations. Christie was a dog-lover. But Tiglath Pileser solves the mystery of how the lights suddenly went out at Miss Blacklock’s house just before the moment of murder.

There were three Tiglath Pileser’s, all kings of Assyria. Tiglath-Pileser I reigned from 1114 – 1076 BCE. He was responsible for much expansion of the Assyrian empire. Little is known of Tiglath-Pileser II, who reigned about a century later. Tiglath-Pileser III seized the Assyrian throne, and took on the name Tiglath-Pileser, in 745 BCE. He reigned for 18 years and also greatly expanded the empire to include much of the Middle East. He is mentioned several times in the Old Testament (2 Kings 15 and 16; and 1 Chronicles 5; 2 Chronicles 28).

Christie almost certainly had Tiglath-Pileser III in mind when she chose the name for Bunch’s cat. In 1949, Christie accompanied her husband, Max Mallowan, on the archaeological dig that Mallowan was leading at Nimrud (Kalhu), which had been a major Assyrian town (it is situated near the river Tigris in modern Iraq). One of the findings were records of provincial administration under the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (see Mallowan memoirs p 256). In his memoirs, Mallowan writes: “But every inch of the acropolis [at Nimrud] is worth re-excavation, including the great Centre Palace of Tiglath-pileser III whose stone bas-reliefs mark an important stage in the history of Assyrian sculpture.”

Goitre

(Emil) Theodor Kocher was the first surgeon ever to win the Nobel Prize. He won it in 1909 for his work on thyroid surgery. He used his prize money to help set up the Theodor Kocher Institute in the University in Bern(e), Switzerland where he had been appointed Professor of Surgery in 1872 at the age of 31 years. The Insitute still flourishes and now carries out research on the immune responses to inflammation. Kocher was a pioneer in the use of aseptic techniques and he made major contributions to surgery in many areas. He was a most meticulous surgeon and this proved to be both a curse and a blessing.

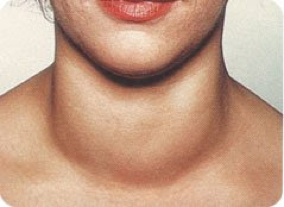

Goitre refers to enlargement of the thryroid gland and is seen as a swelling in the neck. Nine out of every ten cases of goitre worldwide, even today, are due to lack of iodine in the diet. Derbyshire neck was a term commonly used in Britain, up to the 1950s, to refer to a diffuse goitre. Iodine levels in the soil in Derbyshire are low. Until well into the twentieth century goitre was more common in Derbyshire than in many areas of Britain. Similar variations in the prevalence of goitre depending on locality were seen in many areas of Europe and North America. In Switzerland some cantons, such as Appenzell in the east, had a high prevalence of goitre whereas other cantons, such as Geneva in the west, had a relatively low prevalence.

If iodine is given sufficiently early in the treatment of iodine-deficient goitre then the swelling will decrease but if the goitre is well established – if it has been present for many years – then adding iodine to the diet will not reverse the swelling. In that case the only way to reduce the swelling is by surgery to remove some or all of the enlarged thyroid gland. And this is where Kocher’s immaculate surgical technique comes in.

In the late nineteenth century the function of the thyroid gland was not known. Kocher did what few had done before him: he contacted over 100 people on whom he had performed thryoid surgery for goitre to see how they were getting on – a follow-up study. In 1883, at a meeting in Berlin, he reported his findings. He found a distinct difference, on the whole, between those patients in whom he had removed the entire thyroid gland, compared with those in whom he had removed only a part of the gland.

The features of those who now had no gland at all were known then as ‘cretinism’, and would now be called severe chronic hypothyroidism. These people, after the surgery, had gradually become intellectually slow, coarse skinned, and lethargic. This particular and undesirable effect of the surgery was less common after surgery performed by other surgeons and in particular by Kocher’s teacher, Billroth, another giant in the history of surgery.

Billroth was a less meticulous surgeon than Kocher and even when he was intending to remove the whole of the thyroid gland, he rarely did so and unintentionally left parts of the gland, thus reducing the complications due to hypothyroidism. Kocher’s careful surgery had proved to be a curse for some of his patients.The blessing, however, was that Kocher’s work – the total removal of the thyroid gland and his follow-up study – has been crucial in the development of the understanding of the importance and functioning of the thryoid gland.

In 1950, the year A Murder is Announced was published, the American chemist, Edward Calvin Kendall, won the Nobel Prize, in part for his discovery (back in 1914) of thyroxine – the hormone secreted by the thyroid gland: the hormone necessary to prevent the development of ‘cretinism’.

Both the prevention and the treatment of goitre with iodine or iodine-rich foods has a long history. Marine sponges, which would have been rich in iodine, were used by Galen and other Ancient Greek physicians to treat swollen necks. In the thirteenth century de Villanova observed that such sponge treatment reduced the goitrous swelling in young people but had little or no effect once the goitre had been present for several years.

In 1811 the Napoleonic wars led to the discovery of the element iodine by Bernard Courtois. The need for potassium nitrate for saltpetre explosive and the shortage of the traditional source, wood ash, led to its extraction from seaweed. Courtois was investigating the corrosion of the copper vessels he was using to isolate the compounds for saltpetre when he noticed a purple vapour being given off. This led to his discovery of iodine.

In 1813 a doctor from Geneva, Coindet, suggested that the ingredient in seaweed that could prevent and treat goitre might be iodine. Although he started using tincture of iodine to treat goitre there was considerable opposition based on the fear, justified if given in too high a dose, of the dangerous effects of iodine. In 1833 Boussingault advocated using iodised salt as prophylaxis against goitre, although he did not believe that lack of iodine was the fundamental cause of goitre.

It wasn’t until 1851 that another French chemist, Chatin, proposed the hypothesis that iodine deficiency was the main cause of goitre. A few areas in France with a particularly high prevalence of goitre began distributing salt and iodine. In one area iodised salt was given to 5000 school children with goitre and 4000 showed marked or complete reduction of the swelling. But the French Academy of Science remained sceptical of Chatin’s ideas – many other theories of the cause of goitre were proposed – and there were grounds for concern: the doses of iodine being given were very high and many people, especially adults, suffered side-effects, and particularly the effects of too much thyroxine – what would now be called hyperthyroidism or thyrotoxicosis.

It was not until 1922 that the first comprehensive iodised salt programme was started. This was in areas in Switzerland, and the programme has continued until today. A similar programme began in some states in the US in 1924. Britain however has never initiated such a programme. When I was growing up in London in the 1950s my mother insisted on buying only salt that was iodised, which was widely available but not compulsory. Nevertheless the incidence of goitre rapidly decreased between the wars and continued to do so after the Second World War. This was the result of increased iodine consumption not in salt but in milk, because of iodine in cattle feed, and as a result of people eating a much smaller proportion of locally sourced food.