Poirot Score: 81

After the Funeral

☆☆☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

There are weaknesses in the plot and the reader must accept a little suspension of disbelief, but the central ideas are clever and the clues excellent: varied in type, fair, concealed by misdirection. The novel passes the ‘cryptic crossword test’ in that a reader who hits on the solution will be sure that it is correct, but the solution is by no means obvious. The story is good although none of the characters particularly engaging.

Click here for full review (spoilers ahead)

Trivia

Dedication

FOR JAMES in memory of happy days at Abney.

In my copy of the novel there is a typo and the word ‘Abbey’ written instead of ‘Abney’. James is James Watts (see trivia to ABC Murders), the

husband of Agatha’s older sister, Margaret (known as Madge – see Trivia for Roger Ackroyd). See also trivia for Hercule Poirot’s Christmas in which, in place of a dedication, Christie wrote a letter to James Watts. Abney Hall, near Manchester, was the home of James Watts’ parents and later of Margaret and James. Agatha Christie spent Christmas there after Margaret and James were married in 1902. Agatha had met James in 1901 when she was 10 or 11 years old and he was an undergraduate at Oxford. In her autobiography she writes about him: ‘He was kind to me, always treating me seriously, and not making silly jokes or talking to me as if I was a little girl.’

The Voysey Inheritance

Michael Shane laughed suddenly and said: ‘You know, I’m enjoying all this! “The Voysey Inheritance” to the life. By the way, Rosamund and I want that malachite table in the drawing-room’

Chapter 19

The Voysey Inheritance is a play by Harley Granville Barker (1877-1946) first performed in 1905 at the Court Theatre (now Royal Court Theatre) in London. The story centres on a wealthy English family. The play opens in the office of Voysey and Son in the ‘best part of Lincoln’s Inn’ (in London): ‘Its panelled rooms give out a sense of grand-motherly comfort’. One of Voysey’s sons, Edward, is about to become a partner in the firm and has realised that much of the family’s wealth has been funded by his father’s embezzling the money entrusted to him by his clients for investing. When Edward’s father dies, Edward tells his siblings of the situation and seeks their help in righting the wrongs of his father. Each reacts differently, and over the course of the play Edward’s own response, and character, develop.

Michael Shane is reminded of the play by the bickering of the Abernethie family members over who should inherit what after the death of the wealthy Richard Abernethie, and by the surfacing of various long-standing resentments.

Although it is likely that Christie had known The Voysey Inheritance since her youth, it may have been in her mind as she was writing After the Funeral from seeing the 1951 BBC television production starring David Markham as Edward and Allan Jeayes as his father. As an aside, in 1943 Jeayes had played Lawrence Wargrave on stage in Christie’s play And Then There Were None.

Harley Granville Barker started his career as an actor. George Bernard Shaw created several roles for him. When Barker became a theatre director he was particularly interested in plays which tackled social issues and he put on plays by Shaw and Ibsen, amongst others. One of his own plays, Waste, was banned because it tackled the question of the politics of abortion. From early in the twentieth century Barker supported local repertory theatre and also campaigned vigorously for Britain to have a National Theatre. It was not, however, until 1963, seventeen years after Barker’s death, that Laurence Olivier directed the first performance by the National Theatre Company – Hamlet starring Peter O’Toole.

The Voysey Inheritance continues to be performed every generation or so on stage in the UK and in the US. The 30-year-old Jeremy Irons starred in a second BBC version in 1979. The moral, political and social issues raised by the play around questions of privilege and unearned income remain fresh and relevant. The American playwright, David Mamet, adapted the play for a modern context in 2005. The dialogue and discussions are sharp. One line jumped out at me, said by Edward’s lawyer brother, Trenchard: ‘You know every criminal has a touch of the artist in him.’ I was reminded of Mr Shaitana in Christie’s 1936 novel Cards on the Table who says: “A murderer can be an artist … Surely my dear M. Poirot to do a thing supremely well is a justification.”

One of the characters in The Voysey Inheritance says of Edward, to his father: ‘I tell you he’s no use. Too many principles … Men have confidence in a personality, not in principles.’ A sentiment that seems to have been taken to heart by too many of our present-day politicians. Edward himself says: ‘It’s strange the number of people who believe you can do right by means which they know to be wrong.’ Perhaps this is true of Edward himself. His sister-in-law, Beatrice, says: ‘My dear Edward .. I understand you’ve been robbing your rich clients for the benefit of the poor ones?’ to which Edward gently replies: ‘Well .. we’re all a bit in debt to the poor, aren’t we?’

Although a good production will ensure that the play speaks to the modern audience, The Voysey Inheritance, written when Agatha Christie was a teenager, gives a picture of a part of British society in the decade before the First World War which has relevance to the settings of the earlier Christie novels. When discussing her nephews and nieces, Beatrice says: ‘ … they’ll grow up good men and women. And one will go into the Army and one into the Navy and one into the Church .. and perhaps one to the Devil and the Colonies. They’ll serve their country and govern it and help to keep it like themselves ..dull and respectable ..hopelessly middle-class.’

Much of the social comment, however, is given in the stage directions when we hear, perhaps most clearly, Granville Barker’s own voice. These stage directions are unusually full and go far beyond what is needed to enable the directors and actors to play their parts. At the very end of the play we are told that Alice (Edward’s fiancée) ‘leaves him [Edward] to sit there by the table for a few moments longer, looking into his future, streaked as it is to be with trouble and joy. As whose is not?’

Barker, who was a supporter of women’s votes, has this to tell us of Honor – Edward’s sister: ‘Poor Honor … is a phenomenon common to most large families. From her earliest years she has been bottle washer to her brothers. While they were expensively educated, she was grudged schooling; her highest accomplishment was meant to be mending their clothes. Her fate is a curious survival of the intolerance of parents towards her sex until the vanity of their hunger for sons had been satisfied. In a less humane society she would have been exposed at birth.’ And this is how the stage directions describe Edward’s oldest brother (Trenchard) and youngest brother (Hugh): ‘TRENCHARD has in excelsis the cocksure manner of the successful barrister; HUGH the rather sweet though querulous air of diffidence and scepticism belonging to the unsuccessful man of letters or artist. TRENCHARD’S appearance is immense, and he cultivates that air of concentration upon any trivial matter, or even upon nothing at all, which will some day make him an impressive figure upon the Bench [i.e. when a judge].’

Christie and Granville Barker both loved Shakespeare. Granville Barker’s Prefaces to Shakespeare remain valuable essays on the plays providing a thoughtful perspective from an experienced theatre actor and director.

Benger’s

… but there is a gas ring in a little room off the pantry, so that Miss Gilchrist can warm up Ovaltine or Benger’s there without disturbing anybody.

Chapter 18

At the International Health Exhibition of 1884 the Mottershead Company of Manchester was awarded a gold medal for its ‘Peptonizing Fluids and Peptonized Foods’ including a preparation called Benger’s Food.

Peptonizing referred to subjecting a food to artificial partial digestion (predigestion) by means of pepsin, or extract from the pancreas. Pepsin had been discovered by German scientists in the first half of the nineteenth century. It was a component of the gastric (stomach) juices and was found to break proteins (then known as proteids) into the smaller peptones that could be absorbed through the gut and into the body. Pepsin was being given as a medicine for treating digestive problems. A German pharmocopoeia of 1861 has this to say:

‘[Pepsin] has been mass produced for a decade and consumed in great quantities in those places where people are least capable of cooking and eating sensibly – in England and in the United States.’

The pancreas, as well as the stomach, secretes a substance that, even in small quantities, can digest proteins. It also produces another substance that can break down starches into sugars. These various substances became known as ferments, and are now called enzymes.

In the nineteenth century there was increasing concern in many European countries about how to improve the health of the population. During the Crimean War (1853-1856) illness was rife amongst soldiers, with obvious military consequences. Towards the end of the century Dr James Paget calculated that around £11 million was lost to the British economy through reduced productivity caused by illness. Public health became a hot political topic. Some of the focus was on what could be done at Government and local level, such as the provision of clean drinking water. But there was also an interest in what individuals could do for themselves. In the introduction to the food section of the 1884 International Health Exhibition was written: ‘ … our physical well-being is more affected by meat [food] and drink than by any other essential of existence’.

Against this background Benger’s Food was developed. It resulted from the cooperation of three people. Frederick Baden Benger was a pharmaceutical chemist, who trained in London. In 1866 he took over the Mottershead Company in Manchester which supplied equipment to science laboratories and had been founded in 1790. William Roberts was a medical doctor and physiologist who trained at University College, London and then moved to the University of Manchester. Roberts worked on digestion and was more interested in the ‘ferments’ produced by the pancreas than those from the stomach. In a lecture to the Royal College of Physicians he said that the pancreas ‘excels the stomach as a digestive organ’ and can digest ‘the two great alimentary principles, starch and proteids [proteins]’.

Roberts and Benger met and worked together, Benger using his skills to prepare the pancreatic gland extracts for Roberts’ work. Roberts had a eye to the medical applications of his research and Benger had a gift for turning Roberts’ ideas into products. Benger’s Company produced a Liquor Pancreaticus which contained the two main digestive enzymes associated with the pancreas: amylase (which converts starches to sugars) and trypsin (which breaks down proteins). There was, however, a major problem in using this Liquor to treat digestive ailments: the enzymes are destroyed in the stomach before they can provide any aid to digestion. So Roberts conceived the idea of ‘outsourcing’ digestion: that is digesting food artificially, and then giving people the pre-digested food to eat.

Roberts realised that people would only eat such food if it was palatable and so he turned to his wife, Elizabeth Roberts for help. Together they experimented with the Liquor Pancreaticus ‘peptonizing’ various foods. One of these was a mixture of bread and milk which when broken down with the Liquor produced a palatable thin gruel. This was the prototype for Benger’s Food. The final product was a powder to be added to warm milk kept at around blood temperature. It consisted of wheat flour, mixed with pancreatic juice containing presumably the enzymes amylase, that converts the starches in the wheat to sugars, and trypsin, that breaks down the protein molecules in the wheat and milk.

But how to maximise sales? Roberts saw an opportunity to market Benger’s Food not only for those with digestive problems but for all invalids. Here is what Jane Stoker, a lecturer in domestic economy, wrote in 1878, reflecting the received wisdom, about food for people who are ill, for example with a fever:

‘If much food is taken at once, the stomach will make a violent effort to digest it, which effort will be a waste of energy, and will have as a whole the same effect as if the patient had attempted some manual toil which his limbs were too weak to perform.’

The belief was that digesting food takes a great deal of energy (just as walking up a hill might do) and that sick people need to conserve their energy in order to get better. That explains, so it was thought, why ill people so often lose their appetite (and are also not able or willing to walk up a hill). The proper ways to feed invalids became a major concern for doctors, nurses, cooks and those involved in domestic economy. After the Second World War the idea that invalids required a special diet continued but it was recognised that most home cooking was being done by housewives. Marguerite Patten, for example, one of the UK’s first radio and TV cooks and a prolific cookery writer, published her Invalid Cookery Book in 1953 – the same year as After the Funeral. In the introduction, Patten writes:

‘When I recently gave a series of demonstrations on invalid cooking for Television … I was quite unprepared for the almost unbelievable flood of letters and requests for help. As well as the temporary illnesses that occur in every household – influenza, bad colds, childish ailments – there are the elderly who need careful feeding, the members of the family who always watch their diet because of a weak stomach, and the ‘finicky’child, who all present their individual problems in feeding. … I must point out that I am not prescribing any special diet or foods. That is a matter for your doctor, and at all times do ask for his advice and follow it implicitly.‘ [Italics in original]

Amongst the ‘Points to Remember’ at the start of the book, Patten gives these two pieces of advice: ‘Do not consult the patient more than you must about the foods he would like, for when a person is ill, he should avoid extra effort, and sometimes the very fact of being asked to think about food is enough to put him off a meal;’ and ‘Make allowances for sick people being more difficult and fussy about food.’ The book includes sections on dishes for ‘a light diet’, dishes for gastric patients, dishes for the convalescent, and meals to tempt children. In the section on beverages for a light diet, Patten writes: ‘ .. there are many excellent preparations on the market which provide refreshing nutritious drinks – to name just a few: Brands, Bengers, Cadbury’s Bournvita, Horlicks, Marmite, Slippery Elm, etc. etc.’

Benger’s Food was marketed as a food for invalids (and infants) – pre-digested and therefore saving the invalid energy and aiding recovery. It occupied a liminal position between being a food and a medicine. A virtue was made of the fact that the extent to which such ‘digestion’ took place depended critically on the length of time between mixing the Benger’s Food with the milk, and consumption.

An Australian advertisement for Benger’s Food in 1922 stated:

‘Benger’s food is the only food which scientifically combines the two all-important principles of digestion in a dormant state. When you commence to prepare the food by adding hot milk these become active. One modifies the milk making it light as snowflakes [presumably trypsin], the other acts upon the Benger’s food, [presumably amylase] and, while you wait, the two combine in forming a most delicious food-cream, with a delicate biscuit flavor. … There is a world of difference between Benger’s food and pre-digested foods. You must go from pre-digested foods to light, ordinary food at a bound, but with Benger’s you can gradually increase the work of the stomach as it recovers its normal healthy activity’

The belief was that invalids needed food that was easily digestible, and therefore already partly digested, coupled with the idea that the return to normal diet should be staged with a slow increase in how difficult the food is to digest. If Benger’s Food was made by leaving the blood warm milk with the Benger’s Food enzymes for a long time (e.g. 45 minutes) a large proportion of the starches and milk proteins would be already digested thus reducing the ‘work’ of digestion by the invalid. By leaving the Benger’s Food in the milk for shorter and shorter times the amount of predigestion would decrease leaving more ‘work’ to be done by the invalid’s digestive system. It was a kind of training programme back to normality rather like these days we might recommend a gradually increasing regimen of exercise following a period of inactivity.

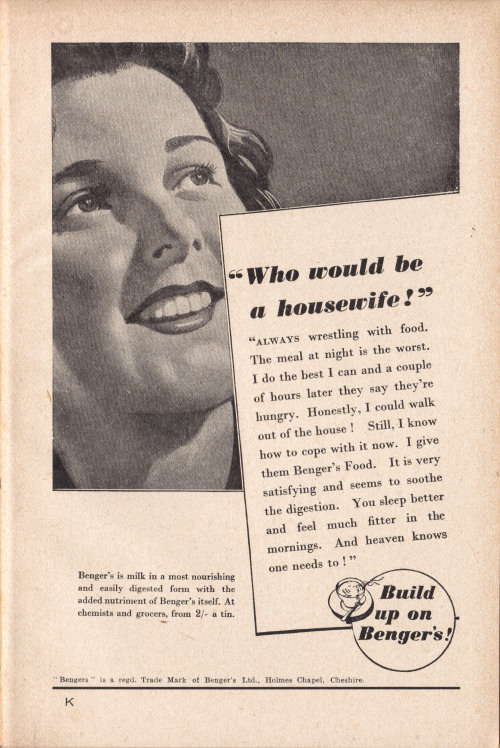

Seeking ever larger sales, by the 1940s Benger’s Food was being marketed as an easy to prepare health food that the busy housewife could give her men folk when they complained of hunger, particularly at night (see advert below).

The concept of requiring special ‘invalid’ diets was going out of fashion by the 1960s. There may have been some truth in the idea that recovery from a severe infection in the days before antibiotics might sometimes have depended critically on diet. It was perhaps the rapid development of antibiotics and vaccines after the Second World War that led to the demise of Benger’s Food. I don’t remember Benger’s Food at all when I was a child growing up in England in the 1950s and 1960s. My mother used to make me junket (milk set with rennet – which amongst other proteolytic enzymes contains pepsin) when I was convalescing from some childhood infection or other in the late 1950s. She no doubt learned to do this from her mother who had trained as a fever nurse during the First World War. Benger’s Food disappeared altogether at some point in the early 1960s.

Benger had acquired Mottershead and Co. in 1870. He renamed the company F.B. Benger and Co. Ltd. in 1891 and again renamed it Benger’s Food in 1903. In 1939 it moved from Manchester to Holmes Chapel (between Stoke-on-Trent and Manchester) and was renamed Benger’s Ltd. Shortly after the Second World War, in 1947, Benger’s Ltd. was bought by Fisons Pharmaceuticals. Fisons was bought by the French pharmaceutical giant, Rhone-Poulenc in 1995. Rhone-Poulenc merged with the German Hoechst AG in 1999 to become Aventis, which itself merged with the French Sanofi to become Sanofi-Aventis in 2004, changing its name to Sanofi in 2011 – with headquarters in Paris. It is currently one of Europe’s largest pharmaceutical companies.

[Much of the information on Benger’s Food comes from Lisa Haushofer’s paper Between Food and Medicine: Artificial Digestion, Sickness, and the Case of Benger’s Food in the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences (April 2018) volume 73, Issue 2, pages 168-187.]

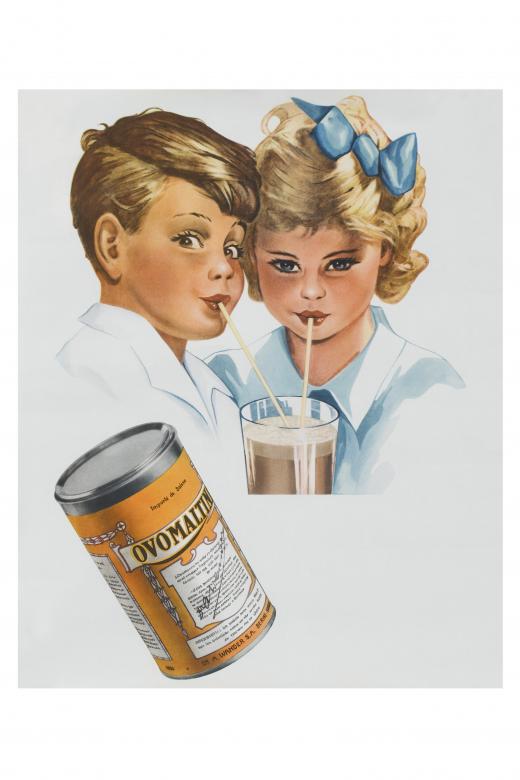

and Ovaltine

By contrast with Benger’s I used sometimes to drink Ovaltine and still do from time to time. It remains popular in the UK and is sold as a powder to be added to hot water or milk. It was never as biologically sophisticated as Benger’s. It became seen as a healthy supplement to the diet associated more with a country farm than a medical laboratory.

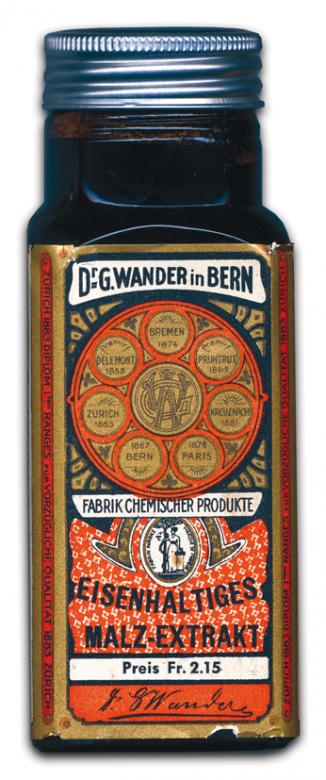

Around 1869 a young chemist, Dr Georg Wander, in Bern in Switzerland started experimenting with the process of malting in which grains, such as barley grains, are enabled to begin germination but not to continue. The grain’s starches are converted to sugars by an enzyme present in the grain that is very similar to the amylase produced by the pancreas of animals and used by Benger. Wander produced a malt extract, a ‘thick, honey-like preparation … free from alcohol or carbonic acid, that contained only the excellent and long-appreciated nutrients of the malt in a concentrated form ’ as Wander himself described it. He marketed this, along with many other products. After his early death in 1897 his son, Albert, took over the business. In 1904 Albert created Ovomaltine made from malt extract to which was added milk, eggs and cocoa before being reduced to powder. Ovomaltine, the name referring to the combination of egg and malt, was first available only as a dietary supplement available from chemists (pharmacies) but it was reclassified as a food and became generally available. It was adopted by the Swiss armed forces in order to ‘strengthen Switzerland’s defences’.

The exact ingredients have varied over time and space. The current British version is made at Neuenegg, just outside Bern in Switzerland, where Ovaltine has been manufactured since 1927. In the UK it no longer contains egg.

In 1909 Albert Wander established a British arm of the company, A Wander Ltd. In Britain the name used was Ovaltine. A British factory was built at Kings Langley in the northern suburbs of London – now just off the M25. The factory was greatly enlarged in the 1920s with the wonderful art deco building which still exists, although as flats – manufacturing ceased in 2002. When Christie wrote After the Funeral in the early 1950s the Kings Langley factory employed 1400 people. At its height the factory was the largest producer of malt extract in the world. Nearby were the Ovaltine Dairy and Poultry farms, the sources of Ovaltine’s main ingredients and used to emphasise the idea of its links to a healthy country life. The farms no longer exist, the land covered to a large extent by the tarmac of the M25. In 1953 the company was still owned by the original business. The company has been bought and sold many times since, passed around like a rugby ball. In many countries, including Britain, it is currently owned by the Swiss company, Wander AG. In 1967 Wander merged with the pharmaceutical company, Sandoz (also Swiss) which merged with the Swiss pharmaceutical company CIBA in 1996 to form Novartis.Twinings acquired the British arm of Ovaltine from Novartis in 2002. Twinings, famous for tea, is in turn owned by Associated British Foods, another British company which also owns the Irish fashion store, Primark. In the US, however, Ovaltine is owned by the Swiss food giant, Nestlé. The journey, from successful family business to but a fragment of one essentially multinational company after another, has become somewhat usual in the years after Christie was writing.