Poirot Score: 76

Dead Man’s Folly

☆☆☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

This book is well clued and fair. It is also an enjoyable read, with much humour from Ariadne Oliver striking sparks off Poirot. Oliver also opens up about her life an an author of detective fiction. Furthermore, Christie pulls of the seemingly impossible task of inventing another original twist to her genre of country house crimes.

Click here for the review (spoilers ahead for this novel and Shakespeare’s Hamlet)

Trivia

Dedication

“To Humphrey and Peggie Trevelyan.”

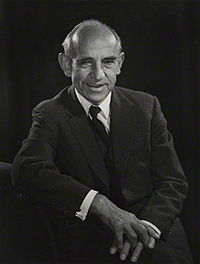

Humphrey Trevelyan (1905 – 1985) and Max Mallowan (1904 – 1978) were schoolboy friends at Lancing College together. They were also contemporaries of Evelyn Waugh.

Trevelyan had an illustrious diplomatic career, including becoming ambassador to Iraq, Egypt, and China. He was Ambassador to Egypt at the time of the Suez Crisis (1956) when this book was published. Perhaps Christie thought it might give him a moment’s respite and cheer.

On retirement Trevelyan was given a peerage. Trevelyan became chairman of the British Museum, and Sir Max Mallowan served on his board of trustees. Many of Mallowan’s archaeological discoveries are in the British Museum.

Humphrey Trevelyan

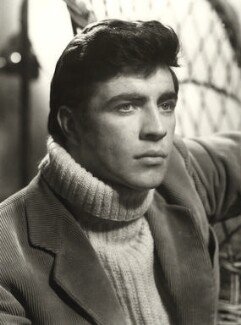

Alan Bates

Angry Young Men in the 1950s

Look Back in Anger, the play by John Osborne, also came out in 1956. Christie was bang up to date with angry young men. I originally thought, reading Dead Man’s Folly that the character of Alec Legge, the angry young atomic scientist having a nervous breakdown with his marriage on the rocks, must somehow be influenced by Osborne’s angry character of Jimmy Porter. Look Back In Anger premiered at the Royal Court Theatre, London in May 1956, and Dead Man’s Folly was published that October. According to various Christie biographies, she wrote Dead Man’s Folly in 1955. Christie, like Ariadne Oliver, was very sensitive to the emotional mood of the times.

The press release for Look Back in Anger described John Osborne as an ‘angry young man’. It was a phrase that described a seismic shift in British theatre. Alan Sillitoe, part of the angry young men drama movement, wrote Osborne ‘didn’t contribute to British theatre, he set off a land mine and blew most of it up.’ An unknown twenty two year old, Alan Bates, landed the part of Cliff Lewis in the original production. Bates was kept on when the play slowly gathered popular acclaim, and indeed transferred to the United States for a run in Broadway in 1957. It made his career. This beautiful picture of Bates is from 1957, no doubt for the American market.

A Folly and Boat Houses

The Gothic Folly, Stowe Gardens, National Trust

One of the many follies in Stowe Gardens

A folly is an architectural landmark, usually on a big estate, to enhance the landscape. There is a really interesting site called The Folly Fellowship, for an in depth discussion of all the different functions, sizes and shapes a folly can be, and lots of beautiful pictures.

In Dead Man’s Folly, the architect points out that the folly was built in the wrong place on the Nasse estate, hidden in the woods. He was perfectly correct. A folly, as shown, was sighted on a hill or rise on open ground to attract the eye. On my cover of Dead Man’s Folly, the artist has elided the ideas of a folly and a boat house, which is rather neat but misleading. I suspect he did not read the book.

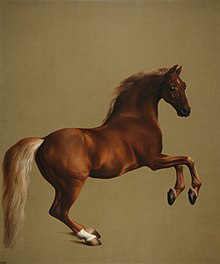

Sir George Stubbs

In Dead Man’s Folly the main character is Sir George Stubbs, a businessman, who buys the Nasse Estate. The Sir George in the book has no interest in art or literature at all. Stubbs asked ‘Betsey Trotwood? Who’s she?’. Christie often quotes Dickens in her books, so not to have read David Copperfield is shorthand for saying ‘this man is a cultural desert’. In Christie novels real people are sometimes mentioned, like Churchill, Stalin and Hitler. This is the first time Christie uses a name for a major character that also was a real famous person. Sir George Stubbs (1724-1806) was an English painter. I cannot see an obvious link between the painter and the character in this book, except they both travelled in Italy and both resolved to come back home as soon as possible.