Poirot Score: 65

Murder in Mesopotamia

☆☆☆

Reason for the Poirot Score

This is a clever variant of a locked room mystery. The clues are fair and good. However, the solution is so improbable that it is not altogether satisfactory.

Click here for Review of Murder in Mesopotamia

Trivia

Katherine Woolley: the real Louise Leidner

Expedition house and staff, 1928-29. Max Mallowan (third from left), Hamoudi, C. Leonard Woolley, Katherine Woolley & cat, Father Eric R. Burrows. {Penn Museum}

Katherine Woolley is portrayed as Louise Leidner in Murder in Mesopotamia. Katherine was very beautiful, intelligent and artistic. She attended Oxford, but left mid-course to train as a nurse in the Great War. Katherine married Colonel Keeling in 1919, and within six months he had committed suicide. Katherine became ill and was examined by a doctor, who then spoke to her husband in private. Keeling went out and killed himself that afternoon. There has been much speculation as to what information was imparted.No one knows what the doctor really said to Colonel Keeling. It is possible that she had androgen insensitivity syndrome, which was not understood at the time, but is actually when a person is genetically male, but looks female. These people are supposed to often be extraordinarily beautiful; a few film stars and supermodels are rumoured to have this condition.

Katherine was interested in archaeology, and volunteered as an assistant at Ur. Seven years after her first disastrous wedding, she married the archeologist Leonard Woolley in 1927. Woolley was the most famous archeologist working in the Middle East at the time, and was knighted in1935.

Leonard Woolley started excavations at Ur, gaining much British publicity. Agatha Christie, who had an interest in archeology and the Middle East since her debutante season in Cairo before the Great War, visited the dig at Ur.

Mrs. Katherine Woolley was a fan of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926). Christie was already a famous, successful author. Perhaps Katherine Woolley thought Christie might usefully fund the dig as an enthusiastic amateur. The Woolleys stayed with Christie in her London house, 22 Cresswell Place, in May 1929. They were friends. Christie returned to Ur, and met a young archeologist called Max Mallowan. Mallowan had known Christie’s nephew, Jack, when they had both been undergraduates at New College, Oxford, together.

Katherine needed to ‘cast a spell’ over men, enjoying feeling her power. She ordered the young men at the dig at Ur to brush her hair! This included Max Mallowan. Dr Joan Oats, another famous archaeologist, is quoted in Laura Thompson’s biography of Christie ‘They actually found this really embarrassing, oppressive, but impossible to refuse’. Katherine would also ask the young male archaeologists to walk ten miles to a souk to buy her two kilos of sweets. Apparently she would eat the lot and then be sick. This is interesting as doctors first recognised bulimia nervosa as an eating disorder in 1979.

Katherine Woolley had ordered Max Mallowan, as a junior in the expedition, to take Christie on a tour of the sights from Ur to Baghdad. Later Christie had to rush back to England as Rosalind, her daughter, had pneumonia. Christie had the message Rosalind was dangerously ill; this was before antibiotics. Christie’s father had died of pneumonia, when Christie had been a child. Max supported the distraught Christie, and accompanied her throughout the agonisingly long four days by train to London, not knowing how Rosalind was. Fortunately Rosalind pulled through. Agatha Christie was 14 years older than Mallowan. They fell in love during this very emotional time.

The despotic power the Woolley’s, especially Katherine, exerted on Max, as a junior member of the dig, when he incurred her displeasure by becoming engaged to Agatha Christie, is almost incredible by modern standards of behaviour. Katherine Woolley would not allow Christie to stay with Max at the dig in Ur, after they were married, or even to come to Iraq at all. Max had suggested that Christie could stay in a hotel in Baghdad, and he could spend weekends with her. This huge influence over juniors at the dig seems vindictive. No wonder Christie took her revenge by killing Katherine off in this book. The character of the quiet American, David Emmott, in Murder in Mesopotamia resembled Max ‘a long humorous face and very good teeth..he looked very attractive when he smiled’.

Mallowan, having gained experience as an archaeologist, and now a man of independent means thanks to Christie’s royalties, could finally escape the Woolley’s thrall. In 1931 Mallowan joined Dr Campbell Thompson’s excavations at Nineveh. The Campbell Thompsons treated the Mallowans with much more consideration. Christie was allowed to be with Max at the Campbell Thompson dig, where she helped as a volunteer, as well as writing Lord Edgware Dies, which she dedicated to Dr and Mrs Campbell Thompson (see Trivia for that book).

Katherine apparently never let Leonard consummate their marriage. She allowed him to watch her having a bath each evening. Woolley asked his solicitor to file divorce papers, on the grounds of non-consummation, but this never happened since Katherine sadly developed multiple sclerosis, and Woolley felt he couldn’t divorce her when suffering such a disease.

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a Greek word meaning ‘between the rivers’. The rivers are the Tigris and Euphrates that flow through modern Iraq. The Euphrates also flows through much of Syria. There is a brilliant British Museum website http://www.mesopotamia.co.uk

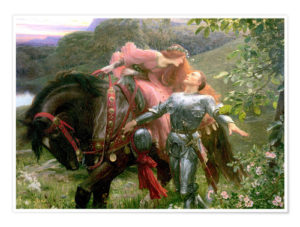

La Belle Dame sans Merci by John Keats 1819

Louise Leidner is referred to as La Belle Dame sans Merci, the beautiful woman without mercy, by two entirely separate characters in the book. Mrs Leidner is the cold, ruthless manipulative woman who craves male attention, and enjoys having men ‘in thrall’, just as Christie saw Katherine Woolley behave at the dig. Clearly this Keats poem was in Christie’s mind when she thought of the characterisation. The original Belle Dame sans Merci poem was by the French poet Alain Chartier in the early 15th century, which gave Keats his title.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

I see a lily on thy brow,

With anguish moist and fever-dew,

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna-dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

‘I love thee true’.

She took me to her Elfin grot,

And there she wept and sighed full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!’

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gapèd wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.