Poirot Score: 55

The Moving Finger

☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

More of a romance than a whodunnit the clues are poor and the specific solution somewhat arbitrary. Although Miss Marple must count as ‘the detective’ she enters the novel over three-quarters of the way through and plays a rather minor part in the whole story. The low score reflects these deficiencies as a detective story. The book however is an entertaining read with some amusing, if not very attractive, characters, good dialogue and acute observations.

Click here for full review (spoilers ahead)

Trivia

Dedication

To my friends Sydney and Mary Smith

Christie knew Sydney and Mary Smith through her (second) husband Max Mallowan who was an archaeologist.

In February 1942 Mallowan, as part of the war effort, was working as assistant to the Senior Civil Affairs Officer stationed at Sabratha – one of the three (tri) cities (polis) of ancient Tripolitania and close to modern Tripoli. In 1943 this area was part of Italian Libya. Mallowan was living in an Italian villa overlooking the sea eating fresh seafood and olives. Christie was living in war-torn London (her Devon house, Greenway, being occupied for use by the military) and eating sausage, potatoes and onion. She spent weekends with various friends including Mary and Sydney Smith (who taught her some algebra).

Sydney Smith graduated from Queens’ College, Cambridge in 1911. He was Keeper of the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum from 1930 to 1948. He moved to the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London in 1948 as the first Professor of Ancient Semitic Languages, a post he held until 1955.

In 1919 the British Museum acquired the Cappadocian Tablets which concern the commercial transactions of a settlement of Semitic traders near Caesarea (in modern Israel) around 2300 BCE. Sydney Smith, an Assistant in the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the Museum at the time, published these texts in three volumes from 1921 to 1925.

Title: The Moving Finger

According to the Book of Daniel (chapter 5) Belshazzar, King of Babylon, made a great feast for a thousand of his lords. He commanded that gold and silver vessels be brought for the feast. These vessels had been taken from the temple in Jerusalem by Belshazzar’s father, Nebuchadnezzar. For this hubris God meted out his nemesis. Before enacting his punishment, God first told Belshazzar what it would be. Whether this was to educate or to add the pain of foreknowledge to the punishment is not clear. God’s method of telling Belshazzar what his fate would be is rather complex. Some disembodied fingers write a message – the writing on the wall – a message that is so difficult to interpret that only one person in the Kingdom seems able to understand it. That person is Daniel. The message tells Belshazzar that he has been weighed in the balance and found wanting. He will die and his kingdom taken over by the Medes and the Persians.

This story lies behind Christie’s choice of title but it is not its direct cause. The title itself comes from Fitzgerald’s nineteenth century English translation, or perhaps more accurately his adaptation, of some eleventh century Persian quatrains by Omar Khayyam – mathematician, philosopher and astronomer. The Fitzgerald ‘translation’ has entered the canon of English poetry. Borges, the Argentinian writer, suggests, as an aesthetic rather than as a religious conjecture, that Omar Khayyam’s soul is reincarnated in England: ‘to fulfill the literary destiny repressed by mathematics’. ‘A miracle happens: from the fortuitous conjunction of a Persian astronomer who condescends to write poetry, and an eccentric Englishman who peruses Oriental and Hispanic books, perhaps without completely understanding them, emerges an extraordinary poet who does not resemble either of them.’ [The Enigma of Edward Fitzgerald, in Other Inquisitions translated by Ruth L.C. Simms, University of Texas Press, 1964].

Omar Khayyam was a significant figure in the history of mathematics. He made advances in algebra and geometry. Christie took lessons in algebra from Sydney Smith to whom she dedicated this novel (see Dedication above). Perhaps it was her interest in Omar Khayyam that led both to the title and to her desire to improve her knowledge of mathematics.

Verse 51 of the Rubaiyat (quatrains) is as follows:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all your Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all your Tears wash out a Word of it

In Daniel the moving fingers are moving because they are writing. In Christie’s novel the moving finger might be the poison pen that points in accusation to each of the inhabitants of Lymstock in turn. It might also refer to the finger that the writer of the letters uses to type the letters, for, in Christie’s novel, these are typed with one finger in order to mask the ‘touch’ of the typist – the pattern in the weights of each letter of the alphabet – a kind of finger-print of the typist.

Shakespeare Sonnets

Megan Hunter begins her letter to the narrator, Jerry Burton, with the opening lines of Shakespeare’s sonnet number 75 [chapter 13]:

So are you to my thoughts as food to life

Or as sweet-season’d showers are to the ground.

In 1942 Christie was reading Shakespeare’s sonnets. In a letter to her husband, Max Mallowan, she wrote [Janet Morgan p242]: ‘What lovely first lines Shakespeare wrote – his “attack” is always more arresting than his climax.’ In that year she wrote a novel (first published in 1948) under the name Mary Westmacott as a present for Mallowan. She called the novel Absent in the Spring from the opening line of another Shakespeare sonnet (number 98): ‘From you have I been absent in the Spring’.

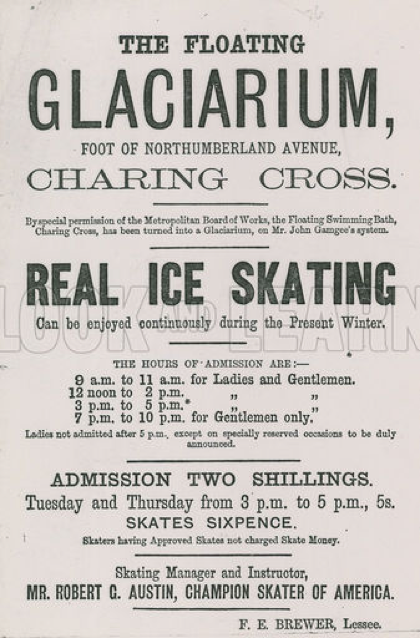

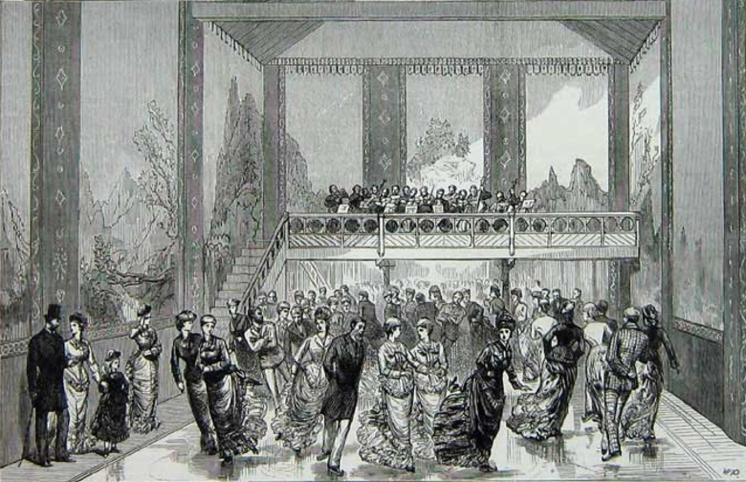

Ice skating rinks

But when I was seven and Joanna two, we went to live in London with an aunt, and thereafter our Christmas and Easter holidays were spent there with pantomimes and theatres and cinemas and excursions to Kensington Gardens with boats, and later to skating rinks

Chapter 1

Skating at indoor ice-rinks became popular in England probably from the early 1930s.

There is evidence that people have skated outdoors on naturally produced ice since 1000 BC. Skating became popular in The Netherlands from the early seventeenth century and was introduced to the English aristocracy later that century following James II’s return from his exile in Holland. The World’s first skating club was founded, probably in the mid eighteenth century, in Edinburgh, and the second in London in 1830.

A spate of artificial skating rinks – the term ‘rink’ being a Scottish word for a course, used in the context of curling – were built in London in the 1840’s but these did not use ice. The surface was a slippery material based on pig’s fat. Their popularity rapidly waned due to the smell, and no doubt the unpleasant results of falling over.

In 1870 a British vet and inventor, John Gamgee, patented a method for freezing meat intended for use in preserving meat imported to Britain from Australia and New Zealand. He adapted this method so that it could be used to freeze water to produce an artificially frozen ice-rink. The first such rink was opened in 1876 in Chelsea, London and was followed by one in Manchester and a significantly larger rink floating on the Thames at Charing Cross in Central London. This rink, however, was not commercially successful and was closed and then scrapped in 1885.

Indoor ice-rinks spread slowly across London from the late nineteenth century becoming rapidly more popular from the late 1920s. There were such rinks at Hammersmith (in the Palais de Danse) and at Empress Hall in Earl’s Court. These closed when the Twickenham and Richmond rink opened in 1928. When it opened it was the longest artificially frozen rink in the world at 286 feet by 80 feet. It was demolished in 1992. When the Grosvenor House Hotel opened in 1929 – still one of London’s most prestigious hotels – it contained an ice-rink (in what is now the Great Room). It was here that Queen Elizabeth II learnt to skate at the age of seven years. The Queens rink opened in Bayswater in 1930 and the Streatham rink in 1931. Both these latter still exist although not as the original rinks. By 1940 there were over 30 indoor ice-rinks in the UK, most in London. Now there are four. In the 1950s, when we were children, my sister and I skated at Streatham. I mostly watched, enjoying my first experience of Tchaikovsky as the live band, like a hotel palm court orchestra, played tunes from The Nutcracker and other ballet favourites.

Fumed Oak

I’ve seen with my own eyes a most delightful little Sheraton piece – delicate, perfect – a collector’s piece, absolutely – and next to it a Victorian occasional table, or quite possibly a fumed oak revolving bookcase – yes even that – fumed oak

Chapter 3 Mr Pye to Joanna about the poor taste of many Lymstock residents

Fumed oak is oak darkened by ammonia vapour. The process was developed commercially at the end of the nineteenth century and became popular in the Arts and Crafts movement. The oak – usually white oak – is placed in a sealed container above a very strong solution of ammonium hydroxide. The ammonium vapour darkens the wood through a reaction with the wood tannins. The extent of darkening depends on the length of time during which the wood is in contact with the vapour (from a few hours to a few days). The darkening does not fade and does not obscure the wood grain. It is said that the process was discovered from the observation that the oak in stables above the horses’ urine became darkened.

Lizzie Borden

See: Trivia for Sleeping Murder