Poirot Score: 50

N or M?

☆☆

Explanation of the Poirot Score:

In historical terms this is a very interesting description of life in Britain in World War II before the USA joined forces. It is a spy thriller rather than a whodunnit, and so cannot be scored highly as there are only a few good clues. Readers fond of the young Tommy and Tuppence Beresford from the 1920s will enjoy meeting the couple again. Unlike Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple who start off old and hardly age over 50 years, the Beresfords and their faithful side-kick, Albert, are now firmly, like Christie herself, middle-aged.

Click here for the N or M? review: plot spoilers ahead

N or M trivia.

Why Christie got into hot water with M15: Bletchley Park, Prof Sir Dilly Knox and Christie:

Tommy innocently asks Haydock:

‘How well do you know Bletchley?’

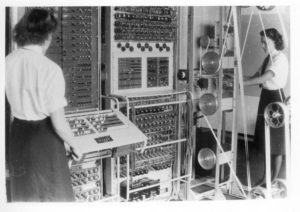

This must have made hearts miss a beat in Whitehall. Prof Knox along with the other code breakers at the top secret Bletchley Park were trying to crack the German Enigma machine ciphers, enabling Churchill and the War cabinet to monitor German commands. When this book was published with its mentions of ‘Bletchley’ and ‘code-cracking’, MI5 were concerned there had been a serious breech of security, and investigated Dilly Knox as the obvious link to Agatha Christie.

Christie’s second husband, Max Mallowan, the archaeologist, worked on digs in the Middle East from 1925-1939 sponsored by the British Museum. Mallowan knew Knox and introduced Knox to his wife, Agatha Christie. Professor Sir Alfred Dillwyn “Dilly” Knox, CMG (1884 – 1943), was one of the leading code breakers Bletchley Park. Knox trained as a classicist, and had been a code breaker in WWI, using his linguistic rather than mathematical techniques. After the Great War, he followed an academic career at Cambridge University in archeological cryptography. He deciphered papyrus fragments.

Marion Hope [nee Whittaker] who worked, like Deborah Beresford, code-cracking at Bletchley Park during the war. Marion was Tony’s mother. Tony is my co-author. Marion never told any of her family what she had done in the war until the story came out in the 1970s. Her name is in the role of honour in Bletchley Park House. Marion read PPE at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, and featured in their exhibition in 2020 on the Bletchley girls at St Hugh’s.

Marion Hope [nee Whittaker] who worked, like Deborah Beresford, code-cracking at Bletchley Park during the war. Marion was Tony’s mother. Tony is my co-author. Marion never told any of her family what she had done in the war until the story came out in the 1970s. Her name is in the role of honour in Bletchley Park House. Marion read PPE at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, and featured in their exhibition in 2020 on the Bletchley girls at St Hugh’s.

According to a new account of the achievements of Bletchley Park – The Codebreakers of Station X, by Michael Smith – MI5 was anxious to find out what Christie knew. It sent officers to question Knox, fearing that if they or the police questioned Christie the investigation was certain to be publicised. Knox said Christie could not possibly know what was going on at Bletchley, but agreed to ask her himself. He invited her to his home in Buckinghamshire. According to friends of Knox, over tea and scones asked Christie why she had named the Indian army major Bletchley.

Christie replied: “Bletchley? My dear, I was stuck there on my way by train from Oxford to London and took revenge by giving the name to one of my least lovable characters.” MI5 was relieved, and apparently took things no further. This is very, very hard to believe!

Knox was dying of lymphoma when they broke the Enigma code in 1941, the year after N or M? was published. He did not live to see the end of the war. His niece was the novelist, Penelope Fitzgerald.

Knox was dying of lymphoma when they broke the Enigma code in 1941, the year after N or M? was published. He did not live to see the end of the war. His niece was the novelist, Penelope Fitzgerald.

Clearly if Hitler had spent time reading Agatha Christies, the whole of WW2 might have been different.

N or M ?

In the book of Common Prayer :

A CATECHISM

THAT IS TO SAY

AN INSTRUCTION TO BE LEARNED OF EVERY PERSON BEFORE HE BE BROUGHT TO BE CONFIRMED BY THE BISHOP

Question. What is your Name?

Answer. N. or M.

The person wishing to be baptized inserts his or her name, or the parents say it.

Foreigners and rising xenophobia

As Britain was at war there is a noticeable antagonism to ‘foreigners’ that Von Deinim finds upsetting, even wishing he was interned to avoid it. Tuppence explains ‘ People cannot distinguish between a Good German and a Bad one’.

It is a theme of Christie books that any foreigner is badly treated by most English people. Poirot himself comes in for a lot of suspicion in previous books, even being found guilty of murder in a Coroner’s court, until the coroner points out he is not accused and was only giving evidence! Foreigners dress and sound different. This ingrained xenophobia was heightened during wartime.

There is deep suspicion of the foreign looking and sounding Vanda Polenska, as a refugee from the central European theatre of War. Christie turns this theme inside out: many ‘traitors’ are fifth columnists.

Haydock bemoans the fact that all the servile foreigners have disappeared:

The war has certainly robbed us of most of our good restaurant service. Practically all good waiters were foreigners. It doesn’t seem to come naturally to the Englishman.

There are also comments about the Irish

but the Irish are terribly perverse. And Sheila is a born rebel

The English come in for criticism too, both those that are traitors, and those that are fooled by them. The Great British Public is unattractively portrayed as made up of tiresome, misogynist Majors, and those unfortunate enough not to be very bright:

an almost imbecile-looking maid, who goggled at Tommy with her mouth open.

I wondered if this poor maid had some medical problem like an underactive thyroid, that these days would be treated.

A Guinea

She would make it half a guinea less

The guinea was a gold coin minted in England from 1663.It was originally worth one pound sterling [£1], which was twenty shillings. Fluctuations in the price of gold relative to silver caused the value of the guinea to increase, as high as thirty shillings, until the price was fixed at one pound one shilling. It was thought the colloquial name ‘guinea’ came from the source of the gold used from Guinea in West Africa. With the turmoil of revolutions and problems with exhausted gold reserves in the late 18th century, the wild notion of paper money, bank notes to denote the gold equivalents, improbably came into circulation as official currency. Real gold coins for large sums of money disappeared into collectors’ cases and hoarders’ strong boxes.

In 1971 the UK’s currency went decimal. The ‘new’ pound had 100 new pence (compared with 240 ‘old’ pence). Shillings (12 old pence) were abolished, as were old pennies. Guineas have clung on by their gold fingertips as a grand vestigial remnant of a more romantic time, mainly in the inflated prices of Oxford and Cambridge May Ball tickets.

People and Places mentioned in this book

This book contains more real events and people than most Agatha Christie novels. Hitler and Stalin are both mentioned, as was the evacuation of the British Forces from Dunkerque, the fall of Paris, and the Blitzkrieg.

There are fictitious places like Leahampton and Leatherbarrow where the action is set. Agatha Christie knew the South Coast of England well as she was born and brought up in Torquay, and had recently bough her home, Greenway, in Devon. She was there when war was declared in 1939. Leahampton may be loosely based on Bournemouth, with its sea-side boarding houses, pier and good train connections up to London.

The Dog and Duck Pub in Soho: 18 Bateman Street, London, W1D 3AJ

In N and M?, Alfred is the publican of the The Duck and Dog, in Glamorgan Street, Kensington, which is very oddly described as ‘South London’. Kensington is north of the Thames, and is usually described as West London. Mrs. Christie had bought several properties and lived at a house in Sheffield Terrace at the time, which is in Kensington, so perhaps this is a private joke.

In N and M?, Alfred is the publican of the The Duck and Dog, in Glamorgan Street, Kensington, which is very oddly described as ‘South London’. Kensington is north of the Thames, and is usually described as West London. Mrs. Christie had bought several properties and lived at a house in Sheffield Terrace at the time, which is in Kensington, so perhaps this is a private joke.

Mrs. O’Rourke’s antique shop called Kate Kelly’s in Cornaby Street, Chelsea. One wonders if this might be Carnaby Street but that is in Soho. Carnaby Street was still in a slum district in the late 1930s: it did not become the centre for the fashionable clothes shops during the Swinging Sixties, thirty years later. Christie sets one of her later novels The Third Girl [1966] in the sex, drugs and rock and roll Chelsea of the 1960s.

The Home Guard (Local Defence Volunteers or LDV)

The LDV: There are various mentions in this book of the network of defences set up in WW II using ex-officers and people either too old or too young for active service.

From 1940 -1944, the Home Guard with 1.5 million local volunteers otherwise ineligible for military service, usually owing to age, hence the nickname “Dad’s Army” – acted as a secondary defense force, in case of invasion by Nazi Germany. The Home Guard guarded the coastal areas of Britain, as well as airfields, factories and explosives stores.

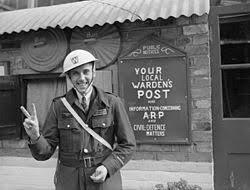

ARP Warden [Commander Haydock]

During the Second World War, the Air Raid Precautions Warden was responsible for the issuing of gas masks, pre-fabricated air-raid shelters, the upkeep of local public shelters, and making sure people observed the nightly blackouts. It was the perfect job for Commander Haydock as it would have enabled him to be out and about during the blackout, and also at the hub of strategic defence planning.

During the Second World War, the Air Raid Precautions Warden was responsible for the issuing of gas masks, pre-fabricated air-raid shelters, the upkeep of local public shelters, and making sure people observed the nightly blackouts. It was the perfect job for Commander Haydock as it would have enabled him to be out and about during the blackout, and also at the hub of strategic defence planning.

[Also see Trivia for The Body in the Library]

Newham Archives and Local Studies Library collection

‘Like a 20th C Blondel in search of his master’: Blondel de Nesle

Albert had seen the Gary Cooper film ‘Wandering Minstrel’ the week before. There is no Gary Cooper film about Richard Coeur de Lion, or Blondel that I could find. There was a Cecil B. DeMille film: The Crusades (1935) with Alan Hale as Blondel and Henry Wilcoxon as King Richard, which was, perhaps in Christie’s mind.

Blondel de Nesle’s name has come down from the 12th Century with some courtly songs. The ludicrous myth that Blondel, a troubadour, visited all the castles in Europe singing outside the windows to try to find where Richard I was imprisoned grew up over time. The story snowballed from the 18th century, with renewed interest in romanticism, and the inclusion of this fiction in poems about Richard I. Rather like Walt Disney and the lemmings, once an false idea has taken hold of the public imagination, it seems impossible to stamp out.

Blondel de Nesle’s name has come down from the 12th Century with some courtly songs. The ludicrous myth that Blondel, a troubadour, visited all the castles in Europe singing outside the windows to try to find where Richard I was imprisoned grew up over time. The story snowballed from the 18th century, with renewed interest in romanticism, and the inclusion of this fiction in poems about Richard I. Rather like Walt Disney and the lemmings, once an false idea has taken hold of the public imagination, it seems impossible to stamp out.

Blondel has even achieved Rock Musical status, written by Tim Rice and Stephen Oliver, in the 1980s.