Poirot Score: 40

Destination Unknown

☆

Reasons For the Poirot Score:

Destination Unknown is a thriller, without any thrills. It is one of only four Christie novels that has never been adapted in for film, screen or stage, out of her oeuvre of over 70 books. There is a startling absence of murders, clues or detectives. Perhaps it should remain Unknown.

Harold Ober, Christie’s US agent, after reading the manuscript, wrote to Edmund Cork her London literary agent, wondering if Christie could be persuaded to ‘rewrite the ending’. This did not happen. The US Saturday Evening Post’s review of Destination Unknown talks of the ‘utterly preposterous’ plot.

This is the low point of Christie’s career.

In the harsh world of best sellers one is only as good as your last book. This failed thriller unfortunately provoked speculation that Christie’s inspiration had finally vanished after thirty years.

Please read on to discover the real communist atomic scientists working at Harwell in the 1950s.

Click here for Review (no plot spoilers as no real plot)

Trivia

Dedication:

‘To Anthony who likes foreign travel as much as I do’

Anthony Hicks was Christie’s new son-in-law. Hicks had married Rosalind in 1949. Rosalind’s first husband had been an RAF pilot killed in 1944 (see Taken at the Flood).

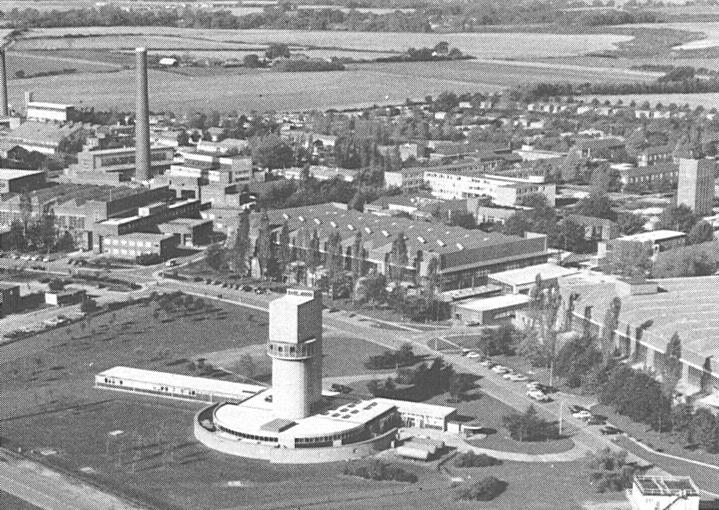

Harwell: Spies, Communists and a chair at Liverpool University?

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment, known as AERE or the Harwell Laboratory, Oxfordshire, was the main centre for atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from the 1940s to the 1990s. Agatha Christie lived in her beautiful house in Wallingford, Oxfordshire, very close to the village of Harwell.

In 1950 the head of theoretical physics at Harwell, Klaus Fuchs, was arrested for spying for the Soviets, and served nine years in prison. This sent ripples of fear across the Western world. Fuchs had escaped to Britain from Nazi Germany in1933 and had gained a DPhil at Bristol University. Fuchs became a British citizen. He then joined the Manhattan Project in the United States of America in 1943. By 1944, Fuchs joined the Los Alamos Laboratory, working on the plutonium bomb. After the war, Fuchs was appointed to help lead the Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) in the UK. If the top British nuclear scientist had been a communist spy, no secrets were safe.

Bruno Pontecorvo was a brilliant Italian physicist. As he came from a Jewish family, he fled the fascists to work in Paris in 1936, and became a member of the communist party. Pontecorvo escaped Paris the day before the Germans entered the city. He spent the war working on nuclear reactors in Canada. After the war he accepted a job at Harwell continuing his research into nuclear fission. After Fuchs’ confession of spying, the backgrounds of all the other Harwell scientists were given careful scrutiny. Pontecorvo had always been open about his communist beliefs. There was no proven evidence that he had spied for the Soviets, but he was felt to be a security risk. It was decided Pontecorvo should no longer have access to Top Secret material. In June 1950, Pontecorvo was offered the new chair of physics at the University of Liverpool. Given an abrupt choice between living the rest of his life in Liverpool or defecting to the USSR, Pontecorvo disappeared with his wife and family.

The Pontecorvos has been on holiday in Italy. Secretly they had flown to Sweden, and then travelled to Finland, and across the boarder into the Soviet Union with the help of Soviet agents.

The Fuchs and then Pontecorvo scandals rocked the very foundations of Western security. One can see, with her previous prescient plot of The Big Four 1927, why Christie was tempted to revisit the theme of nuclear physicists defecting to another power.

Christie in ‘Destination Unknown’ acknowledges the difficult working conditions at Harwell. The Intelligence officer, Wharton says:

Security precautions. The feeling of being perpetually under the microscope, the cloistered life. They get nervy, queer…They being to dream of an ideal world. Freedom and brotherhood, and pool-all-secrets and work for the good of humanity! That’s exactly the moment when someone, who’s more or less the dregs of humanity, sees their chance and takes it!..Nobody’s so gullible as the scientist.

The Atlas Mountains and Leper Hospitals

The story ends in a secret establishment hidden within a leper hospital in the high Atlas mountains. Leprosy is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae, an acid-fast, rod-shaped bacillus. The disease mainly affects the skin, peripheral nerves, the lining of the upper respiratory tract, and the eyes. Since pre-Biblical times leprosy has been feared as a contagious disease, thousands of years before the transmissibility of the infectious agent was finally understood. Leprosy flourishes in tropical and subtropical climates, so had a high prevalence in the Middle East.

Leprosy is now curable, and treatment in the early stages can prevent disability. When this book was written in 1954 there was a new treatment, dapsone. Throughout history, people afflicted with leprosy have been ostracised by their communities and families. Leper hospitals in mediaeval Europe were always more than 2 miles outside towns, an extreme form of social distancing. The Oxford Leper hospital was founded by Henry I in 1179, and upgraded by the 14th C. It was built well outside the walled city of Oxford, in the countryside along the path to Cowley.

Christie was clever in setting her top secret research lab within a leper compound. No one would go there.

In 2016 WHO launched its Global Leprosy Strategy 2016–2020: Accelerating towards a leprosy-free world. Sixteen million people suffering from leprosy have been treated in the last 20 years worldwide.

Christie travelled extensively in the Middle East from 1910-60s. People with leprosy would have been a familiar sight. I worked for a short time in a leper hospital in Southern Africa in 1979. Each leper was given a cat to look after and sleep with as they were admitted. The cat’s job was to prevent rats and mice gnawing off that person’s fingers and toes whilst they slept.

The last person I saw with leprosy was sitting on the outside steps of Rouen Cathedral, France in 2010.