Poirot Score: 94

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

☆☆☆☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

This is a classic of detective fiction. The originality of the solution is famous. The brilliance is not simply in this originality but in pulling it off. In order for the solution to work Christie had to solve difficult narrative problems, and she had to be fair to the reader. She was writing in uncharted territory. The ways in which she overcame the narrative problems are outstanding. But this is also a first-class puzzle. There are many clues and these are complex in the sense that individually they do not point to the solution, but taken together they form a number of excellent ‘clue structures’. Furthermore the solution is the only solution that accounts for the great majority of the facts and clues: readers who guess the solution for the right reasons will be almost certain that they are correct, but the solution is not easy to guess. The novel is also special in being the first of Agatha Christie’s fully mature whodunnit novels.

Full Review (spoilers ahead)

Click here for full review (spoilers ahead)

Trivia

Dedication

TO PUNKIE: who likes an orthodox detective story, murder, inquest, and suspicion falling on everyone in turn!

Punkie is Christie’s elder sister, Madge. Christie had two siblings: a sister, Madge (11 years older), and a brother, Monty, (ten years older). Madge was already at boarding school when Agatha was born: at Miss Lawrence’s School, Brighton, which was later to become Roedean. Madge had had several stories published in Vanity Fair before Agatha had published, and in 1924 Madge’s play The Claimant had a run at The Queen’s Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue, London. Agatha is thought to have been somewhat jealous of her sister’s writing success. Madge married James Watts, who possibly gave Agatha the idea for Ackroyd (see full review). Agatha dedicated The ABC Murders (published in 1936) to James Watts.

Agatha Christie’s sister, Margaret ‘Madge’

Portrait by William Logsdail, 1928

[http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/

magaret-madge-frary-miller-18791950-mrs-james-watts-100286]

Mah Jong Parties

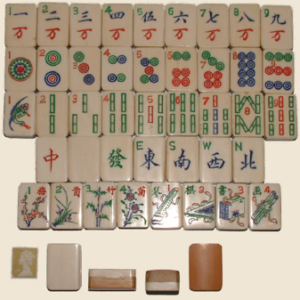

Chapter 16 is called An Evening at Mah Jong. ‘This kind of simple entertainment is very popular in King’s Abbot. The guests arrive in galoshes and waterproofs after dinner. They partake of coffee and later of cake, sandwiches and tea.’ Dr Sheppard, rather clumsily, knocks down the rack that held his pieces.

Mah Jong – a Chinese game played with tiles and having some features in common with the card game rummy – was discovered by the West in the early twentieth century. Mah Jong parties, such as that described by Christie, became popular in North America and Britain in the 1920’s. Abercrombie & Fitch was the first company to sell Maj Jong sets in the US. The British version of the game more closely resembled the Chinese form than did the US version.

Mah Jong tiles

[http://www.mahjongbritishrules.com/sets/examples/set1.html]

Vacuum Cleaners

In chapter 3 Caroline Sheppard says of Hercule Poirot, her neighbour: ‘I believe that he’s got one of those new vacuum cleaners’. Vacuum cleaners developed slowly from carpet cleaners in the second half of the nineteenth century. Probably the first motorised cleaner that sucked in air was created by Hubert Cecil Booth in 1901. By the 1920’s there were several companies, both American and European, making domestic vacuum cleaners.

The Hoover Building in West London, an Art Deco icon built in 1932,

for the manufacture of vacuum cleaners. A few years ago it was a Tesco’s supermarket

but has now been converted into apartments.

Dipsomaniac

‘To put it bluntly, Mrs Ackroyd was a dipsomaniac’(chapter2). The word dipsomaniac meaning a person who is addicted to alcohol was in common use in British English until the 1970s but is now rarely used.

Tapis

In chapter 2 Sheppard writes: ‘I don’t know what Mrs Cecil Ackroyd thought of the Ferrars affair when it came on the tapis’. Tapis means cloth, usually with colourful designs, including tapestry. ‘On the tapis’ is the English translation of sur le tapis meaning, literally, on the tablecloth, and metaphorically, as here, under discussion or up for discussion.