Poirot Score: 70

They Do It with Mirrors

☆☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

A large cast of characters whirl around in this book, distracting the reader from the rather straightforward plot. Just as a stage magician distracts their audience from the mechanism of a trick. It is a classic ‘locked room’ murder mystery with a classic Christie twist.

The rich Carrie Louise has been married three times, and has two daughters with her first husband (one adopted, one genetically theirs). Carrie Louise’s adoptive daughter died in childbirth, but the grand daughter, Gina and her husband live with Carrie Louise at Stonygates, along with many staff members. Carrie Louise has two stepsons from her second marriage to the lothario, Johnnie Restarick. Alexis and Stephen Restarick are grown up, and are characters in this story. At the time of the action in this book, Carrie Louise is married to her third husband, Lewis Serrocold. Lewis Serrocold, philanthropist, has turned Stonygates into an Institution for the rehabilitation of Juvenile Delinquents. Christie sets out the moral question of mad versus bad for English society post-war through the ever alert eyes of Miss Marple . It is well clued.

Click here for Review (plot spoilers for this novel, and Shakespeare’s King Lear ahead)

Trivia

A short History of Juvenile Delinquency:

With the onset of the industrial revolution, British society changed. People were required to work in mills rather than tend the plough. Dickens writes passionately about the plight of children in poverty in the inner city slums of Victorian England: his father was in debtors’ jail. In Oliver Twist, the ‘artful dodger’ is a classic juvenile delinquent, long before the term was coined. From the 1880s reformers were pressurising Government to change the structure of legislation for children, which went with a new view of ‘childhood’ as being something worth protecting. In 1893 The Child Study Movement was founded by psychologist James Sully. Child psychology and psychiatry followed behind adult psychiatry as a means to understand antisocial behaviour. People were split between believing behaviours were dictated by the genetic code of that individual, or acquired from the environment that child was brought up in. The nature versus nurture controversy, that is still hotly debated today.

The Children Act of 1908, created special Juvenile Courts. Boys Clubs were developed where privileged male undergraduates were encouraged to volunteer to help in clubs in the slum districts, as good role models for poor boys. Wodehouse wrote about them in his novels from the 1920s.

The first Child Guidance Clinic started in 1927 on Bell Lane in Spitalfields, East London supported financially by the Jewish Health Organisation. This was long before the NHS. The clinic worked closely with the Inner London Juvenile Court nearby. Dr Cyril Burt had been appointed as psychologist to the London County Council and came to be a pioneer in the field of educational and social psychology, although his later career was blighted by controversy. Burt argued in The Young Delinquent (1925) that delinquency was caused by neglect and poor parenting. He advocated the use of child guidance clinics by all juvenile courts as a means of preventing future recidivism. Burt was the first British psychologist to be knighted.

Like all radical ideas, the momentum took a long time to be accepted by the mainstream. The 1948 Children Act, seventy years after the start of this particular social reform activity, advocated that children and young people who broke the law should be reclaimed and rehabilitated. No doubt public debate about this recent legislation gave Christie the nidus for this novel.

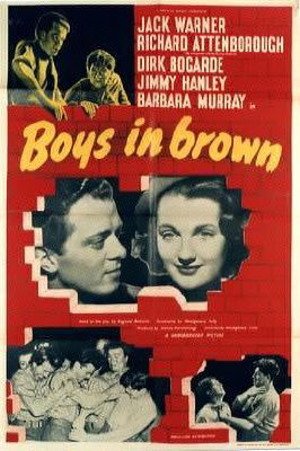

There was a British film The Boys in Brown [1949] with a spectacularly stellar cast of very young actors: Richard Attenborough, Dirk Bogarde and Jimmy Handley. These teenagers end up in a borstal run by a benign prison governor (played by Jack Warner). This might also have fired Christie’s imagination.

Porcelain Tea Services

‘white utility cups mixed with the remnants of what had been Rockingham and Spode tea services.

The Serrocolds in the novel are oblivious to aesthetic beauty.

There was a huge interest in precious porcelain in the wealthy of Europe from the 18th century. Jane Austin writes about tea services in Northanger Abbey. The English potteries managed to copy Chinese porcelain, when drinking tea became an expensive and hence fashionable past time. The Rockingham factory started in Yorkshire in 1745 and closed in 1842. The Spode factory started in Stoke-on-Trent in 1770 and is still making fine china today.