Poirot Score: 74

The Body in the Library

☆☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

There are two main clues with some supporting additional clues to the main plot twist, which is clever and simple. These clues are clear but well hidden. They are perhaps a little concrete compared with Christie at her best. The complete solution is, however, less well clued and alternatives are plausible. The main setting – a hotel on England’s south coast – is well conceived and although there is some humour this is not Christie at her comic best.

Click here for full review (plot spoilers ahead)

Trivia

Minoan Fourteen Car

“When was the last time you saw … your car? What make is it, by the way?” “Minoan Fourteen.”

Chapter 9

Christie often mentions the names of cars. Sometimes these are real cars, sometimes the names are made up. The made up names are often based on reality, as in the reference to ‘Brixwell, South London’ (chapter 4), clearly an amalgam of Brixton and Stockwell. There has never been a car make called Minoan – let alone one so popular that there would have been eight Minoan 14s in the courtyard of the Majestic Hotel, and described as the ‘popular cheap car of the year.’

The Fourteen refers to the car’s power measured in horsepower. Car models at the time were often designated by their horsepower. Several popular makes of British cars developed models in the 1930s which achieved fourteen horsepower, for example: the Austin 14, Vauxhall 14, Standard 14, Morris 14 (pictured), and the Wolseley 14 (which was a re-badged Morris). Most of these models had engines from 1700cc to 1850cc.

The term Minoan – from the mythical Cretan Minotaur – was coined, at least in the archaeological context, by Arthur Evans to describe the Bronze Age civilization on Crete. Evans excavated Knossos from 1900. Agatha Christie’s second husband, Max Mallowan, a distinguished archaelologist started his career as apprentice to Leonard Woolley. Woolley in turn was a protégé of Evans’. All three had close connections with the University of Oxford. The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has one of the finest collections of Minoan artefacts outside Greece thanks to Evans’ gift – Evans had been Keeper of the Museum in the 1880s. Christie would certainly have known this collection well. Indeed she and Mallowan may well have met Arthur Evans who lived at Boars Hill, just outside Oxford, and who died in 1941, around the time this novel was written. Morris cars were made at Cowley, a suburb of Oxford (where the BMW Mini is now assembled). Christie had owned at least one Morris car. One of the best known models was the Morris Minor, manufactured from 1928 to 1934 (and again after the war). I like to think – and this is pure speculation – that the name Minoan Fourteen was a result of Christie’s mind associating her archaelogical interests, Oxford, the popularity at the time of cars with fourteen horsepower, and the name Morris Minor. Perhaps one of their archaeological friends used a Morris Minor for touring and nicknamed it the ‘Minotaur’.

The Brighton Trunk Murders

You see, Sir Henry, it seems to me that there’s a great possibility of this crime being the kind of crime that never does get solved. Like the Brighton trunk murders.

[Miss Marple to Sir Henry Clithering, chapter 11]

There were three unrelated “Brighton trunk murders”. In 1831 John Holloway murdered his wife, Celia, and took her remains in a trunk in a wheelbarrow to Preston Park in Brighton and proceeded to bury her. He was found guilty and hanged. Miss Marple, however, is not referring to this murder but to two murders that took place in 1934.

The first was discovered when a malodorous trunk at the left luggage department of Brighton’s railway station was opened. The dismembered body of a pregnant woman in her 20’s was found. Her legs were later discovered in a case at Kings Cross station in London. She was never identified and her murderer never prosecuted although a local doctor who carried out abortions was suspected.

In the second case the murdered body of Violette Kaye was found in a trunk in the lodgings of her male friend, Toni Mancini, near Brighton railway station. Mancini was prosecuted. The junior prosecuting counsel was Quintin Hogg, later a senior Conservative politician. The senior defence counsel was Norman Birkett. Mancini was found not guilty but confessed to the murder to a journalist shortly before his death in 1976.

Elisabeth Bergner and Vivien Leigh

She was going into Danemouth for a film test. … He wanted a certain type, and he told Pam she was just what he was looking for. … It was a kind of Bergner part, he said. ….. He told her about Hollywood and about Vivien Leigh – how she’s suddenly taken London by storm, and how these sensational leaps into fame did happen.

(Chapter 17)

Elisabeth Bergner (1897 – 1986) was a stage and film actor born in what is now Ukraine, brought up in Vienna, and after living in Zurich and then Berlin came to London where she married the screen writer and film director, Paul Czinner in 1931. They became British citizens in 1938 and helped many jewish actors escape from Nazi Germany. JM Barrie wrote a play for her (The Boy David) in 1936. She starred in several British films including Stolen Life (1939) with Michael Redgrave. The story involves identical twin sisters, Sylvina and Martina Lawrence (both played by Bergner), and was remade, as A Stolen Life, in 1946 starring Bette Davis. Bergner was later effectively stalked by a young actress who called herself Martina Lawrence. Bergner told the writer, Mary Orr, about this experience who based a short story, The Wisdom of Eve, on the anecdote. The film, All about Eve (1950), was in turn based on that story. The film stars Bette Davis as the Bergner character.

Bergner was known for ‘trouser roles’ following great success as Rosalind in As You Like It first in Zurich and then Berlin – in which she played Rosalind for a record 566 consecutive performances. She was also successful as Viola in Twelfth Night, Ophelia in Hamlet (not of course a trouser role) and in Brecht plays. ‘A kind of Bergner part’ may refer to her somewhat androgynous appearance or to the mix she could bring of being both gamin – almost still a child – and also a femme fatale. Her performance as Rosalind is available on DVD – opposite a very young Laurence Olivier as Orlando, script adapted by Barrie, and score by William Walton. Watching the film with modern eyes I do not find it easy to understand the great success that she had in this role.

Vivien Leigh (1913 – 1967) is perhaps best known internationally as Scarlet O’Hara in Gone with the Wind but she was seen frequently on the London stage following her first success in 1935. She became friendly with Laurence Olivier and after eventually obtaining divorces from their respective spouses they married in 1940. They co-starred in plays and films including simultaneous productions of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra. Vivien Liegh became increasingly troubled by mental and physical illness. Olivier and she divorced in 1960 and she died in 1967, the cause being given as tuberculosis.

William Dobbin

Mark Gaskell said, “Hugo McLean it is. Alias William Dobbin”

(Chapter 12)

William Dobbin is a character in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. He is a rather unattractive pathetic person whose love for Amelia is not requited although in the end they marry. Hugo McLean’s devotion to Adelaide Jefferson in The Body in the Library seems similarly unrequited although the implication at the end is that they will marry.

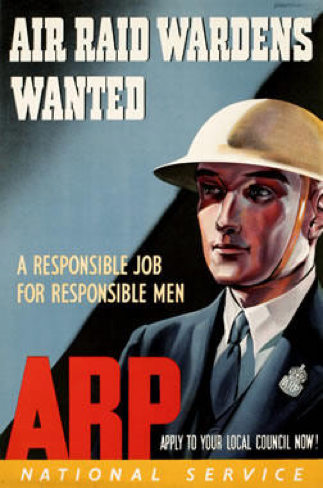

ARP Work

(See also the Trivia to N or M, and A Murder is Announced)

I’ve heard a good deal about Basil. He did ARP work, you know, when he was only eighteen. He went into a burning house and brought out four children, one after another. He went back for a dog, although they told him it wasn’t safe.

(chapter 20)

ARP stands for Air Raid Precautions. Following the First World War, and the success of German bombing raids over Britain, there was considerable concern in Britain about what defences there could be to bombing in any future war. The Air Raid Precautions was set up as early as 1924 and became more active as the possibility of another war became more likely during the 1930s. Following the bombing of the basque town of Guernica by the German air force at the request of the Spanish nationalist government in 1937, the British Government was predicting that there could be one million British casualties in the first month of a war. In 1939, shortly after war was declared, the Government ordered one million coffins to be made.

The purpose of ARP was to boost morale and effective defense against bombing raids. Air Raid Wardens were the cornerstone of the ARP. There were wardens for each sector (there being about ten sectors for each square mile in London). These were local people who, once war started, were responsible for registering everyone in their sector, for ensuring that the blackout was enforced, for shepherding people to the nearest shelter, and for first-aid if needed after the bombing. They worked closely with fire and ambulance services.

Basil Blake was presumably involved in the ARP before the war and helped with non-military emergencies as in the anecdote about the burning house.