Poirot Score: 83

Evil Under the Sun

☆☆☆☆

Reasons for Poirot Score

This is a rich novel replete with clues and misdirections. The central puzzle – how could anyone have had the opportunity to commit the murder – is engaging and cleverly answered. Although the correct solution is not the only possible there are some subtle clues and one that is unusually complex in its structure. We see Poirot rather more interested in the opposite sex than is usual, and Christie allows her wit and humour full rein.

Trivia

Dedication

“TO JOHN In memory of our last season in Syria”

“John” probably refers to John Cruickshank Rose. He was an architect and draughtsman who, with Christie herself, had been part of a small team under the leadership of Christie’s (second) husband, Max Mallowan, in 1933. With funding from the British Museum they excavated the site of Arpachiya in Mesopotamia in modern Iraq. For political reasons Mallowan subsequently turned his interest to sites in Syria. In 1937 and 1938 he led the first excavation of Tell Brak in northeastern Syria, and John Rose was again one of the party. It was here that Christie was writing Murder is Easy. Again local political problems resulted in the party moving a hundred miles to the west to the Balikh Valley where they carried out the first archaeological excavations. This was probably the ‘last season in Syria’ to which Christie refers.

John Rose provided illustrations for the booklet Excavations at Tall Arpachiya 1933 and for the book The Pyramids of Egypt written by IES Edwards and published as a paperback by Penguin in 1947. Rose went on to become a successful architect. After the fire in 1948 that destroyed much of Castries, the capital of St Lucia, he coauthored the Report on the New Town Planning Proposals: Redevelopment of Central Area, Castries, St Lucia and played a major role in the rebuilding of the city. After the war he often entertained Christie and Mallowan at his home in the Barbados. Christie also dedicated her 1964 novel, A Caribbean Mystery, to him. [See: Janet Morgan, p206, 213-214; and http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/online_tours/middle_east/agatha_christie__archaeology/agatha_christie__archaeology.aspx]

Breach of Promise

They say Lord Codrington was absolutely infatuated with her. It was understood they were to be married as soon as the decree was made absolute. Actually, when it came to it, he didn’t marry her. Turned her down flat. I believe she actually sued him for breach of promise. [Chapter 2]

Prior to 1753, marriage in England and Wales was governed by canon law of the Church of England. The only absolute requirement for its validity was that the marriage had to be celebrated by an Anglican clergyman. Many young couples became legally married in secret (clandestine marriages), without the knowledge or consent of their parents. The Marriage Act 1753 (known as Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act) aimed to put an end to such secret marriages. For the first time marriage became regulated under statute law and the requirements for a valid marriage were tightened and made explicit. The practice of clandestine marriages was much reduced, although since the Act did not apply to Scotland young English or Welsh couples wishing to marry without parental consent could cross the border into Scotland and become legally married. After the construction of a toll road in the 1770’s, the most popular Scottish border village for such elopements was Gretna Green.

The question arose as to whether, if a man promised to marry a woman and then subsequently refused to do so, the woman had any legal redress. In England and Wales, between 1753 and 1970 there were several hundred such cases brought to the common law courts, many of which were successful: that is, the woman received some compensation. The main grounds for such compensation were due to the loss of the woman’s expectation to be materially supported by a husband. The extreme social stigma relating to unmarried women who had lost their virginity also played a part in providing grounds for compensation.

There had always been considerable dispute over the question of whether it was right for courts to intervene in personal relationships in this way. As social standards relating to women in the workplace, and to premarital sex, changed so support for breach of promise as a legal category diminished. The Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1970finally abolished actions of breach of promise of marriage in England and Wales by stating that an agreement to marry is not a legally enforceable contract.

The Wallace Case

He’s not the kind that shows anything. That sort makes a bad impression in the witness box, and yet it’s a bit unfair on them really. Sometimes they’re as cut up as anything and yet can’t show it. That kind of manner made the jury bring in a verdict of Guilty against Wallace. It wasn’t the evidence. They just couldn’t believe that a man could lose his wife and talk and act so coolly about it. [Inspector Colgate talking to Colonel Weston and Hercule Poirot about Kenneth Marshall – Chapter 5 part V]

In 1931 William Herbert Wallace was convicted, at the Liverpool Assizes, of the murder of his wife, Julia. At his trial he had appeared unusually lacking in emotion. In an almost unprecedented move, this conviction was overturned by the Court of Criminal Appeal on the grounds that the conviction was not supported by the weight of evidence – in other words that the jury had got it wrong. Wallace died of renal failure in 1933. No one else was ever tried for the murder of Julia Wallace. There have been several attempts to solve this crime. Some believe that William Wallace did commit the crime and got away with it but most of those who have studied the case are of the opinion that he did not. A junior work colleague of Wallace’s, Richard Parry, has been implicated but died in 1980 without ever admitting to the crime.

The Wallace case has been cited in other crime fiction. Christie’s fellow member of the Detection Club and contemporary, Dorothy L Sayers mentions it in The Anatomy of Murder; and P.D. James refers to it in The Murder Room. Raymond Chandler, in a letter to Carl Brandt wrote about real crime cases: “ .. the best cases that I’m really familiar with are English. Three of the best of all time, and certainly my three favorites, because of their huge elements of doubt, their strange characters and the richness of their background, are: the Wallace case, which I would call the Impossible Murder …” [Raymond Chandler Speaking, edited by Dorothy Gardiner and Kathrine Sorley Walker. University of California Press: Berkeley. 1997].

Photos

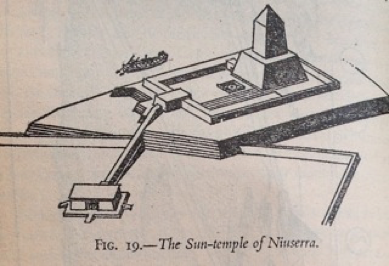

John Cruickshank Rose: The cover and title page of The Pyramids of Egypt Penguin first edition 1947 to which Rose contributed the diagrams and pictures, and one of his pictures – on p136]

Philip Yorke, First Earl of Hardwicke (1690 – 1764) who was Attorney-General and then Lord Chancellor through successive administrations. He was mainly responsible for the Marriage Act 1753. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Yorke,_1st_Earl_of_Hardwicke]

William Wallace after his successful appeal against the conviction of murder. [ http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/wallace.html ]