Poirot Score: 75

Hercule Poirot’s Christmas

☆☆☆☆

Reasons for Poirot Score

Two sets of clues must be combined in order to solve this mystery. The solution is not easy but the clueing is fair and a reader who puts all the clues together can be pretty confident of having succeeded. The motive is unconvincing, the mechanism contrived and the characters, humour and story less engaging than most Christie books so I have not given this novel as high a Poirot score as it would deserve if based solely on the clues.

Click here for full review (spoilers ahead)

Trivia

Dedication

In place of a dedication there is a short letter to “My dear James” and signed “Your affectionate sister-in-law”. James is James Watts (see trivia to ABC Murders), the husband of Agatha’s older sister, Margaret (known as Madge – see Trivia for Roger Ackroyd).

Take your seats for first lunch

An attendant pushed his way along the corridor [of the train].

‘First lunch, please. First lunch. Take your seats for first lunch.’

The seven occupants of Pilar’s carriage all held tickets for the first lunch. They rose in a body and the carriage was suddenly deserted and peaceful.

The first Pullman car with a complete kitchen was called the Prince of Wales and was added to the Leeds express and began service in 1879. The meals were cooked over an open fire at the end of the carriage. The last call for the dining car on a British train was not that long ago: it was on the 19.33 from Kings Cross to Leeds on 20 May 2011.

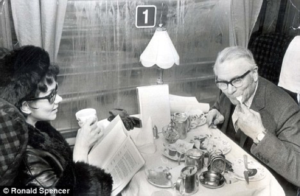

I remember in 1968 travelling from Oxford to London and having tea served at my table in a silvered teapot. The picture shows the actors, Lawrence Olivier and Joan Plowright (Lord and Lady Olivier), in 1970, eating on the train between London and Brighton.

“First lunch, please” would not be heard on a modern British train. If you are lucky a trolley carrying poor quality chocolates, biscuits and sandwiches will pass by your seat with a depressingly small choice of mediocre drinks. Or you may walk to the train ‘shop’ where the choice of what you can drink from a thin plastic cup will be only slightly better.

Simeon Lee’s delight in his own wickedness

“Ah, but I’ve been more wicked than most.’ Simeon laughed. ‘I don’t regret it, you know. No, I don’t regret anything. I’ve enjoyed myself . . . every minute! They say you repent when you get old. That’s bunkum. I don’t repent. And as I tell you, I’ve done most things . . . all the good old sins! I’ve cheated and stolen and lied . . . lord, yes! And women – always women! Someone told me the other day of an Arab chief who had a bodyguard of forty of his sons – all roughly the same age! Aha! Forty! I don’t know about forty, but I bet I could produce a very fair bodyguard if I went about looking for the brats!”

Simeon Lee is straight out of an Elizabethan drama, derived perhaps from Shakespeare’s Aaron the Moor, Richard III, Don John or Iago, or from Marlowe’s Barabas.

Christie enjoyed taking part in amateur dramatics as a teenager and loved Shakespeare particularly.

Burne-Jones Knight

“His face had the mild quality of a Burne Jones knight. It was somehow, not very real” [said of David Lee, Part 1 section IV]

As can be seen from the two Burne-Jones’ pictures below, these two knights, one St George slaying the dragon and the other the Florentine ‘Merciful Knight’, have similar profiles.

Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833 – 1898) was an English Pre-Raphaelite artist and designer and close associate of William Morris.

Hock and Claret

‘Hock or claret?’ murmured Tressilian in a deferential whisper in Mrs George’s ear. Out of the tail of his eye he noted that Walter, the footman, was handing the vegetables before the gravy again – after all he had been told! [Part 3 section lll]

These days the question would be ‘red or white’ but at formal meals until well after the Second World War the choice of wine at the start of the meal would normally be hock or claret.

Hock is German white wine. The word hockamore was an anglicization of Hochheimer referring originally to wine from Hochheim on the river Main near Frankfurt. It was shortened to hock a term in use at least since the seventeenth century. The term became more loosely used to denote wines from along the Rhine as well the Main. In 1864 one writer (Taylor in the book Words & Places) complained: “It would be curious to trace the progress of the perversion whereby the wines which in the fifteenth century used to be correctly designated ‘wines of Rhin’ have come to be called Hocks. Hochheim … lies on the Main and not on the Rhein.” [Oxford English Dictionary] The ‘perversion’ got worse. By Christie’s time of writing the term was widely used to refer to any German white wine sold in Britain, and as the picture shows is no longer even restricted to German wines. Jancis Robinson writes: “It has been by no means uncommon for the same wine to be offered as Hock to a gentlemen’s club and Liebfraumilch to a supermarket buyer”.

The term claret is still in common British use to refer to red wines from the Bordeaux region of France although it is sometimes used (or misused) to refer to other red wines considered to be of similar style. The original use of the term, in contrast with Hock, was less restricted by region than it generally now is.

Trade in wines from the Bordeaux area to the British Isles has flourished since medieval times and many of the modern Bordeaux chateaux have been owned by the British and Irish. The first wines imported from this region to Britain in the medieval period had short fermentation periods and only a few days in contact with the grape skins so they were pale in colour – like a modern rosé – and known as vinum clarum, bin clar which became clairet in its anglicization. By the sixteenth century this had become claret. In the second half of the seventeenth century rather better wines, darker, and limited to the sandy soil around Graves and the Médoc and made on specific properties (often centred on chateaux) were being imported into Britain – the New French Clarets. The modern use of the word claret now normally refers to these wines.

Sodium citrate and blood clotting

You had with you a bottle of some freshly killed animal’s blood to which you had added a quantity of sodium citrate. [Part 6, section IV]

Sodium citrate has played an important part in the history of blood transfusion. Once the circulation of the blood around the body had been established by William Harvey in the first half of the seventeenth century experiments attempting to transfuse blood started to be carried out. Christopher Wren, more famous as an architect than scientist, experimented with injecting various fluids into the veins of animals and in 1665 demonstrated to the Royal Society, which he had helped to found, the transfusion of blood from one animal to another. In 1667 Jean-Baptiste Denys in Paris and, a few months later, Richard Lower (picture below), in Oxford and London, carried out the first animal to human blood transfusion. Blood transfusions on humans were made illegal in both France and Britain later in the century because of the very high human mortality.

It needed developments in the understanding of immunology – the recognition of various blood types in particular by Karl Landsteiner in 1900 – and in preventing blood from clotting, before human blood transfusion could become safe and routine. The development of blood transfusion became urgent during the First World War. In 1914 Adolph Hustin showed that the addition of sodium citrate to blood prevented it from clotting. In 1915 Richard Lewisohn determined the toxicity level for citrate in dogs and in 1915 Richard Weil showed that citrated dog’s blood would remain fluid and could be transfused two days later. Peyton Rous and Joseph Turner were able to keep stored rabbit blood for two weeks and then transfuse it. Blood banks were becoming a possibility.

Although there are now many anticoagulant agents, citrates are still in use. Sodium citrate is the anticoagulant in the tubes used to collect blood for testing its clotting properties. Free calcium is required in the blood for clotting to take place. Citrates work by binding the calcium thus preventing clotting.

Photos

Dining car

Burne-Jones, St George, in the William Morris Gallery in London

Burne-Jones’ watercolour of The Merciful Knight in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, England.

http://www.bmagic.org.uk/objects/1973P84

Californian ‘hock’

http://weimax.com/old_bottle_gallery-1.htm

A selection of various clarets

Portrait of Richard Lower by Jacob Huismans from the Wellcome Collection

http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/richard-lower-16311691-anatomist-126016