Poirot Score: 89

Death on The Nile

☆☆☆☆☆

Explanation of the Poirot Score:

This is one of Christie’s most complex novels, with utterly brilliant cluing. You can solve it, feeling confident you have the right solution before the dénouement, and get a real sense of achievement by doing so.

Click here for Review [plot spoilers ahead]

Trivia

Names:

Christie always had a feel for names. She stated that once the name of a character was right, the rest of the writing followed. Sometimes her characters change names during drafts of a book, if she was uneasy with them. I was immediately alerted to the name Signor Rachetti. I remembered Mr Rachett in Murder on the Orient Express, whose real name was Cassetti, and wondered if Christie had realised she’d made an interesting elision to Rachetti for this man.

The Temples Of Abu Simbel:

The famous Temples Remises II, finished in 1264 BC, are not now where Agatha Christie and Max Mallowan saw them in the 1930s. The carved sandstone temples were moved to higher ground; a massive operation in the 1960s by UNESCO with archaeologists from all around the world helping to dismantle and reassemble the blocks. The Aswan Dam, built to conserve the waters of the Nile, then flooded the valley floor where the Temple complex had stood in Christie’s day.

In the 3000 years since the Temples had been built, the complex had become covered in sand, so only the massive famous statues stood out, partly buried. In 1817, the Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni dug the sand away, re-discovered the temple complex and described it to a wondering Europe. Perhaps this is why Christie chose an Italian archaeologist for her book. Napoleon’s exploits in North Africa had set off an ancient Egyptian craze in Europe. Tourists have been visiting the Temples ever since, as the height of exotic travel, romance and culture. What better place for a honeymoon?

What Doctors and Nurses Take on Holiday?

As doctors ourselves, when we go on holiday we pack paracetamol, disinfectant, plasters and travel insurance, if travelling abroad. What on earth was Dr Bessner, a ‘nerve specialist’, these days a psychiatrist,specialising in neurosis, doing with a case of ‘long, delicate, surgical’ knives, along with his Baedeker? No psychiatrist I know would dream of operating on any one, ever. Nor would any body I know consent to a psychiatrist performing surgery on them.

The 1929 Baedeker of Egypt has been described as the best travel guide ever, so its rather pleasing it gets a mention in this 1930s book: it is now highly prized by book collectors.

Nurse Bowers “gave her {Jackie} a shot of morphia”. Morphine or heroin are more modern names of this opiate. This again, to modern medical readers, is one of the most shocking things in the book. What was Nurse Bowers doing with morphine injections in her handbag? We never get any clues that Marie Van Schuyler is terminally ill, nor in chronic pain. Was Miss Van Schuyler a secret morphia addict? There are many morphine addicts in Agatha Christie novels {see, for example, Peril at End House}. In the 21st Century you require special letters to clear surgical instruments and dangerous drugs through customs. Indeed many countries in the Middle East will not allow morphia into their country in your luggage, even with medical documentation. Nurses today would never give an injection of morphia to someone to calm hysterics. Neither would anyone medical give an opiate without a doctor’s written drug chart, and in the UK at least, checked with another nursing professional first. The administration and regulation of ‘dangerous drugs’ has changed in 80 years.

For what dentists take on holiday please read Death in the Clouds.

Fictional Female Novalists

Mrs Salome Otterbourne may be seen as Agatha Christie’s caricature of herself as a romantic novelist. Christie wrote bitter ‘romantic’ novels under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott. Unlike Salome Otterburne, she was moderately successful, but didn’t get on the international best seller lists as her detective fiction Christies did. Salome Otterbourne is Christie’s ying to Ariadne Oliver’s yang; Christie’s lady detective novelist. We get treated to some wonderful humour in fictional romantic titles such as ‘Snow on the Desert’s Face’: ‘Powerful – suggestive. Snow – on the desert – melted in the first flaming breath of passion’. Christie uses ‘Under the Fig Tree’, a previously published Otterbourne, to poke fun at thoughtless book jacket designers, who draw a naked woman under a tree with ‘leaves of an oak, bearing large improbably coloured apples’. Christie was always insistent on checking her book covers prior to publication. I was shocked to see a paperback cover of Lord Edgeware Dies with this cover: no gun comes into the story at all. Presumably Agatha Christie is spinning in her grave.

For a discussion on what is a Dragoman: see Appointment with Death Trivia

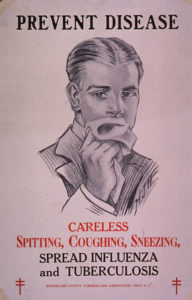

Consumption: tuberculosis [TB].

Tim Allerton is described as ‘consumptive’: a term that has dropped out of common usage, but was still prevalent in my childhood in the 1950s. It meant tuberculosis: a disease that ‘consumed’ you from the inside. Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin achieved the first genuine success in immunization against tuberculosis in 1906, using attenuated bovine-strain tuberculosis. It was called bacillus of Calmette and Guérin (BCG). The BCG vaccine was first used on humans in 1921 in France, but only received widespread acceptance in the USA, Great Britain, and Germany after World War II: after this book was written. In 1946, nearly a decade after this book was written, the discovery of an antibiotic, streptomycin, suddenly brought hope of an effective treatment, even a cure to millions of sufferers.

Tim Allerton is described as ‘consumptive’: a term that has dropped out of common usage, but was still prevalent in my childhood in the 1950s. It meant tuberculosis: a disease that ‘consumed’ you from the inside. Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin achieved the first genuine success in immunization against tuberculosis in 1906, using attenuated bovine-strain tuberculosis. It was called bacillus of Calmette and Guérin (BCG). The BCG vaccine was first used on humans in 1921 in France, but only received widespread acceptance in the USA, Great Britain, and Germany after World War II: after this book was written. In 1946, nearly a decade after this book was written, the discovery of an antibiotic, streptomycin, suddenly brought hope of an effective treatment, even a cure to millions of sufferers.

In France in the 1800s it was estimated that about 25% of the population died of TB: hence all the operatic heroines dying in the arms of their lovers, improbably singing with enough lung capacity to fill Covent Garden, just before they expire on stage.

With improved nutrition and public health measures, the rate of death by the 1930’s had dropped in Europe to about 10%, but almost everyone had been infected. As a medical student in the 1970s, I could see this on every chest X ray of local Oxfordshire people who had been born before the 1940s. The Ghon focus would show up on a chest X ray, as a little white plaque, against the darkness of normal lung tissue, like a bright star in a dark night. This represented the childhood TB infection walled off in the lungs, and calcified with age. Some people had a ‘consumptive’ episode, like Mr. Allerton, most people had no idea they had been previously infected. The cure, in the pre-antibiotic era, was to try to boost the body’s immune system by rest, fresh air and good food. Sanatoriums sprung up for the wealthy in the Alps, or by the English seaside for the middle classes. As always, the poor just died. The human body’s immune system can often wall off the infection in the lung, to stop it spreading throughout the body. The person would always be slightly weakened, but could manage a normalish life. Working in Southern Africa in 1979, it was a shock to find every patient had active TB.

Since 2005 the advent of fully antibiotic-resistant TB has again raised research in this area for better vaccines. About 1/3rd of the World’s population still have TB.

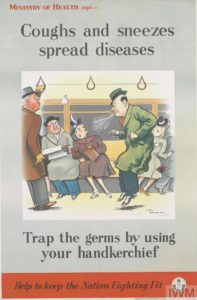

The ideas of good personal hygiene: ‘coughs and sneezes spread diseases’ was drummed into us as 1950s children, from adults who feared TB and knew people who had died from that disease. With the sudden appearance of Covid 19, new generations are suddenly learning basic hygiene again.

The Second Miss Marple that never was?

From her biographies it is suggested that Death on the Nile started off as the second major Miss Marple novel. It is not clear why Christie changed her plans and put Poirot back in Egypt. Miss Marple as a famous detective came very slowly into Christie’s writing. First in 1927 in a short story, The Tuesday Night Club [see blog on The Murder at the Vicarage]. Then a full length novel: Murder at The Vicarage [1930], then in 1934 another short story. This failed Marple novel, from 1937, shows that Christie kept thinking of the elderly spinster from St Mary Mead, trying to find a comfy place for her to knit and think. Christie wrote ‘Sleeping Murder’ in 1940, but the book was not published until 1976, after Christie’s death.