Poirot Score: 70

Cards on the Table

☆☆☆

Reasons for the Poirot Score

The solution is somewhat arbitrary with only one good hard clue, which although suggestive it is not definitive. The clues and solution do not meet the cryptic crossword clue criterion. But, Christie was trying out something new and daring. She was experimenting with purely psychological clues: trying to fit the method of the crime to the psychological profile of the suspects. Even though the experiment failed – in the end she had to rely on non-psychological clues – she was, as so often, pushing at the boundaries of the whodunnit. She was ahead of her time both with regard to detective fiction and real police work in highlighting ‘offender psychological profiling’. In addition the set-up of the novel is good and there is a great deal of humour. For all these reasons we have given the novel a higher Poirot Score than we would have given if based solely on its quality as a whodunnit.

Click here for full review (spoilers ahead)

Trivia

Mrs Ariadne Oliver

Cards on the Table is the first Christie novel in which Mrs Oliver appears. She is a character in six further novels. She has, however, already appeared in a Christie short story called The Case of the Discontented Soldier. This was first published in 1932 in the US in the magazine Cosmopolitan and later that year in Britain in the magazine Woman’s Pictorial. It was published in the book of short stories Parker Pyne Investigates in 1934. In Cards on the Table Mrs Oliver is a feisty successful crime novelist who is forthright in her views. Her novels feature her Finnish detective Sven Hjerson. “I only regret one thing” she says, “making my detective a Finn. … I am always getting letters from Finland pointing out something impossible that he’s said or done. They seem to read detective stories a good deal in Finland. I suppose it’s the long winters with no daylight. In Bulgaria and Romania they don’t seem to read at all. I’d have done better to have made him a Bulgar.” She says a number of things about writing crime novels much of which sounds as though it is Christie straight from the heart. Here are some examples.

“Writing is not particularly enjoyable. You actually have to think. And thinking is always a bore.” [Chapter 17]

“Some days I can only keep going by repeating over and over to myself the amount of money I might get for my next serial rights.” [Chapter 17]

“I did have a secretary … I felt she knew so much more about English and grammar and full stops and semi-colons than I did, that it gave me a kind of inferiority complex. Then I tried having a thoroughly incompetent secretary, but, of course, that didn’t answer very well, either”. [Chapter 17]

“I could invent a better murder any day than anything real. I’m never at a loss for a plot.” [Chapter 4]

But Mrs Oliver is not Agatha Christie. It is certainly not true of Christie that: “I’ve written thirty-two books by now – and of course they are all exactly the same really..” [Chapter 8] And Christie makes fun of Mrs Oliver’s reliance on ‘feminine intuition’.

Mrs Oliver in The Case of the Discontented Soldier is described as: “the sensational novelist”. She is the authoress of “forty-six successful works of fiction, all best sellers in England and America, and freely translated into French, German, Italian, Hungarian, Finnish, Japanese, and Abyssinian.” In that story two people – a man and a woman – have separately answered an advert: “Are you happy? If not, consult Mr Parker Pyne”. Parker Pyne decides that he wants to bring these two people together for romance. Ariadne Oliver creates the scenario to bring them together. This involves the woman being kidnapped. The kidnappers are actors employed by Parker Pyne but both the woman and the man think it is for real. The man is told to meet someone and it is arranged that on the way he will hear the screams of the woman. He rescues her and they marry, unaware to the last that the whole scenario had been arranged.

Photo: Zoe Wanamaker as Mrs Oliver in the Poirot TV series. http://www.mirror.co.uk/tv/tv-previews/agatha-christies-poirot—itv1-256641

Criminal Psychological Profiling

Poirot’s, and Christie’s, approach to identifying the murderer in Cards on the Table is primarily to match the crime with the psychology of the suspects. This kind of psychological criminal profiling has become popular in fiction since the 1990s through book and film (e.g. The Silence of the Lambs) and TV dramas (e.g. Cracker, Criminal Minds). The first serious use of ‘offender profiling’ seems to have been by London’s Metropolitan Police in the 1880s (see for example: http://www.forensicpsychology.net/resources/criminal-profiling/ ; and: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_the_Ripper). There had been a number of murders of prostitutes, followed by mutilation of the bodies, in the Whitechapel area in London. Many of these murders were clearly committed by the same person who has been popularly known as Jack the Ripper. Dr Bond, a physician who had examined the bodies, was asked in 1888 to give his opinion on the murderer’s surgical skills. He wrote a report for the police in which he concluded that the murderer did not possess the skills of either a doctor or a butcher. He also stated that he thought the murderer would be middle-aged, quiet and harmless in appearance and neatly attired. The serial killer was never identified. It was not until 1972 that the first behavioural unit was established in the US at the FBI headquarters in Virginia. The value and basis of criminal profiling (offender profiling) remains controversial. Its use is in the possible identification of groups of people to investigate rather than in providing specific evidence of guilt. Christie appears to have been ahead of her time in exploring criminal psychological profiling, and it is perhaps prophetic that she found, in her fictional world, that she had to rely on non-psychological clues to provide the hard evidence.

Imperial and moustache

The description of Mr Shaitana’s appearance (chapter 1) includes:

“ ..he wore a moustache with stiff waxed ends and a tiny black imperial.”

Poirot is jealous of this moustache: it is, we are told, the only moustache in London that could, perhaps, compete with that of M. Hercule Poirot. Whether Poirot would have had the courage to compete in The World Beard and Moustache Championships (had they existed in his day) is a moot point. These Championships define several categories of moustache, including the Imperial which is characterised as: Small and bushy with the tips curled upward. Hairs growing from beyond the corner of the mouth must be shaved.[http://www.worldbeardchampionships.com/imperial-moustache-2011/ ]

This is not the meaning of the word, however, in Cards on the Table. Mr Shaitana has a moustache (that is, hair on the upper lip) and ‘a tiny black imperial’. An imperial in this sense is hair just below the lower lip. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as: “A small part of the beard left growing beneath the lower lip”. The word was imported into English directly from the French impériale.

Photo: http://rupee3naans.wordpress.com/2008/12/01/the-beard-chronicles/

Baluchistan

‘Where are you going to? asked Mrs Oliver.

‘A little shooting trip – Baluchistan way.’

Poirot said, smiling ironically:

‘A little trouble, is there not, in that part of the world? You will have to be careful.’ [Chapter 19]

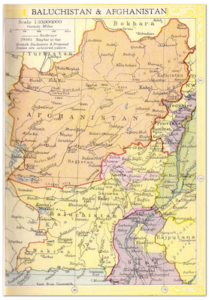

Baluchistan was the area to the west of Karachi in the borders of modern Pakistan and Iran and just south of Afghanistan. The area became a British protectorate in 1876 (and was extended northwest along the Persian/Iranian and Afghanistan border in 1893). It formed the south western border of British India. In 1947 the area was incorporated into (West) Pakistan and normally spelt Balochistan.

The ‘trouble’ to which Poirot refers is probably the dreadful earthquake of 1935 which centred on Quetta – the largest city in the area – and killed around 50,000 people. It is possible that Poirot is referring to military ‘trouble’ as Baluchistan is just south of the Northwest Frontier where the British were fighting the Mohmand tribes in the mid-1930s.

Photo: Map of Baluchistan and Afghanistan 1935 (when Agatha was writing Cards on the Table). [http://www.philatelicdatabase.com/asia/afghanistan-baluchistan-map-1935/]

Revolver, automatic; Dictograph, phonograph

‘ .. I don’t see that it matters if I … say a revolver when I mean an automatic, and a dictograph when I mean a phonograph.’ [Mrs Oliver, chapter 8]

Mrs Oliver is probably expressing Christie’s own irritation with people who write to tell her that she has made an error in one of her stories.

A Dictograph is a proprietary name (hence the capital D) for an instrument that records sound in one room, by means of a microphone, and transmits that sound to a loudspeaker in another room. This enables a person to eavesdrop on a conversation in another room. The forerunner of baby cry detectors. A phonograph, in the sense here, is the instrument patented by Thomas Edison in 1877, and subsequent developments, for reproducing sound that has been recorded and preserved on some kind of material object such as a wax cylinder (in the original) or a record. Probably in Christie’s British context in the 1930s synonymous with gramophone (later record player and then perhaps CD player).

Revolvers and automatics are pistols that allow more than one shot to be fired without manual reloading. In the case of a revolver there is a set of cartridge chambers (typically four or six) which revolve such that each chamber is presented in front of the hammer successively. Automatic is an abbreviation of automatic pistol and often includes semi-automatic pistols. Such a pistol has a mechanism for continuously and automatically loading, firing and ejecting a cartridge as long as the ammunition is supplied. The energy from one shot is used to eject the cartridge and load the next bullet from the magazine [See: Oxford English Dictionary].

Photos Phonograph, 1899, for playing cylindrical records. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phonograph_cylinder]

Dictograph, around 1940, for recording speech. [http://www.ssplprints.com/image/131220/exton-david-dictograph-loudspeaking-master-house-telephone-unit-c-1940]

Parlourmaids and housemaids

Dr Roberts describes his household to Superintendent Battle.

I live here with a cook, a parlourmaid and a housemaid. [Chapter 9]

After the First World War the number of households with living-in servants in Britain rapidly decreased. As is clear, however, from this passage, and from other Christie novels, servants remained a feature, up to the Second World War, not only in aristocratic houses but also in professionals’ households, such as that of Dr Roberts. The more servants in the household the more specialised was each position. When Isabel Fitzherbert Randall moved, with her husband, from England to Montana in the hope of making a fortune, she ended up with no help in running the house. “Here I am, cook, parlour-maid, house-maid, and scullery-maid all rolled into one” she wrote in her book: A Lady’s Ranche Life in Montana, published under the initials I.R. in 1887.

A housemaid is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as; “A female domestic servant, having charge especially of the reception-rooms and bed-rooms”. A parlour-maid as: “A female domestic servant who waits at table in houses where indoor men-servants are not kept”. The scullery is “the department of a household concerned with the care of plates, dishes, and kitchen utensils” and so a scullery maid is in charge of such care. Households might also include a chambermaid: “A female servant in a house or inn, who attends to the bedrooms”.

Wallingford

Miss Meredith, one of the four suspects, lives with her wealthier friend, Miss Rhoda Dawes, in Miss Dawes’ house: Wendon Cottage, Wallingford. In chapter 29, Major Despard visits the cottage: “He went through the garden and across the fields, and turned to the right along the towpath.” A short time later Battle and Poirot take another route to the towpath and the river and witness what was probably an attempted murder.

Wallingford is an attractive market town on the River Thames between London and Oxford. It is where, in 1934, Christie bought Winterbrook House, with its Queen Anne front and a Georgian back. It had a long garden that stretched down to the river. There is a museum in Wallingford that has a room devoted to Agatha Christie.

Photo: Winterbrook House, Wallingford [http://www.booksplease.org/2009/09/21/in-celebration-of-agatha-christie/]

Evipan

‘A simple restorative? – N-methyl-cylco-hexenyl-methyl-malonyl urea,’ said Poirot. He rolled out the syllables unctuously. ‘Known more simply as Evipan. Used as an anaesthetic for short operations. Injected intravenously in large doses it produces instant unconsciousness. It is dangerous to use it after veronal or any barbiturates have been given.’ [Chapter 30]

Christie was up-to-date and accurate. Evipan, a trade name for the barbiturate hexobarbitone (or hexobarbital), was produced by the German company Bayer – the company that marketed the first barbiturate, Veronal, in 1903. Evipan was isolated in 1932. In 1933 and 1934 there were many reports of its use as an anaesthetic in the British journal The Lancet. There was interest in the use of intravenous anaesthetics to replace those administered as a gas. Evipan is a barbiturate but unlike veronal (barbitone) and most other barbiturates at the time it is broken down rapidly in the liver making it ideal as a short term intravenous anaesthetic. Evipan was also attractive as an anaesthetic because it has a wide margin of safety. The lethal dose was around four times the dose needed for effective anaesthesia. Death is from respiratory failure: the drug depresses breathing to dangerously low levels. It is true that the lethal dose would be diminished if the person had already taken another barbiturate.

Quite what Christie’s source of information was is unclear. In the publications in The Lancet the scientific name is given differently with ‘barbituric acid’ replacing ‘malonyl urea’. In a publication in 1934 in The American Journal of Surgery the scientific name is given as Poirot expresses it, in his unlikely but impressive show of knowledge. In the US and Canada however the common name for the drug was Evipal whereas in Britain and the rest of Europe it was known by the name Poirot gives: Evipan. Perhaps Christie knew of the drug from a secondary source rather than the original professional publications. Christie had been trained as a pharmacist’s assistant and had passed apothecary exams, and it is clear that she kept abreast of pharmacological developments relevant to crime fiction.

References:

Jarman R, Abel AL (1933) Evipan: An Intravenous Anaesthetic. The Lancet: 222, 18-20.

Jarman R, Abel AL (1934) Evipan as an Intravenous Anaesthetic: Results in One Thousand cases. The Lancet: 223, 510-513.

Livingston EM, Emy S, Lieber H (1934) Evipal Sodium: A Short Intravenous Anaesthetic. The American Journal of Surgery: 26, 516-521.